Part II: Mrs. America and the Georgia Fight over ERA Ratification

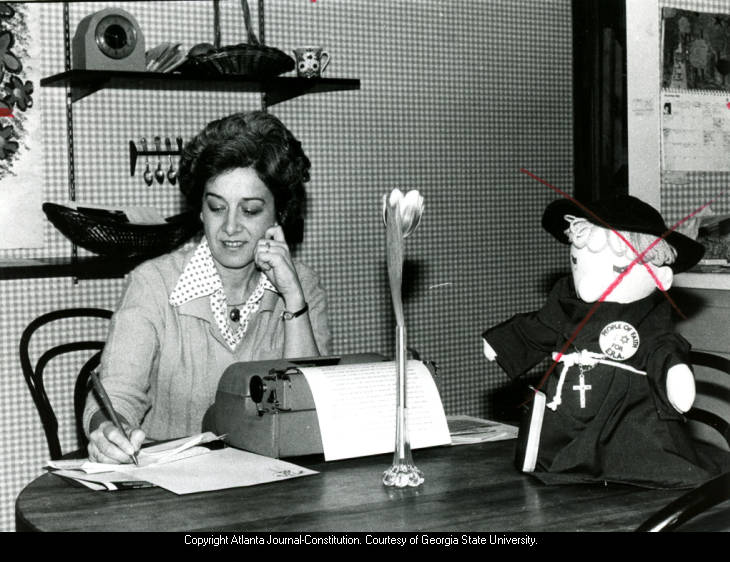

Stop ERA Georgia Chairman Katherine Dunaway pinning a badge on W. M. Goodson, 1979.

This April, we were scheduled to debut the exhibit ERA: Absolutely Yes in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Collections at Georgia State. While postponement of the exhibit and panel discussion has happened, conversation on the history of the Equal Rights Amendment builds in response to a new television show, Mrs. America. The first part of this interview covered general impressions of the show, writing the history of women’s lives, Phyllis Schlafly’s motivations, the importance of print culture to the movements, and historian Robin Morris’s meeting with Schlafly. This post covers the second of a three-part conversation with Morris, archivist Morna Gerrard, and exhibit curator Samantha Harvel. We discuss the importance of state politics as a hinge between grassroots and national movements, shifting political identities in the 1970s, the woman who switched sides, and the formidable organization of STOP ERA forces in Georgia.

Connecting a national movement with the grassroots

Conn: Robin, in your article “Organizing Breadmakers: Kathryn Dunaway’s ERA Battle and the Roots of Georgia’s Republican Revolution” you write, “A focus on women in the ranks of national leadership provides valuable information into the changing make-up of political parties, but it obscures the incalculable contributions of women at the grassroots level. However, a study of the grassroots participation likewise misses the large national sweep.” That was a fascinating point your article keeps coming back to that, if you think about the ERA in terms of a massive national movement that then just gets localized in Georgia, you miss something important. Still, if you think about it only in terms of something local without the national context, you also miss vital information. So you seem to be saying that there’s something about this ERA ratification fight explicitly that connected local and national politics. Where and how do you see this overlap between the local and national in terms of what we see in Mrs. America and the local, Georgia fight over ratification?

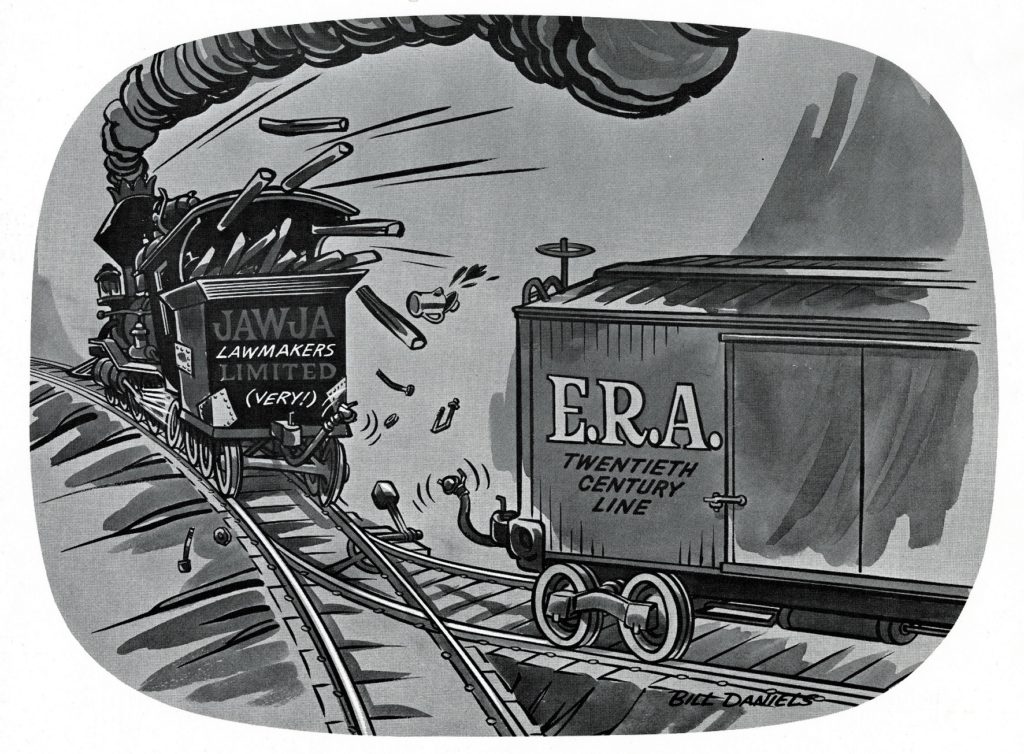

Morris: I do think that’s one that the show is missing and it may get into it. I’m really excited for the Houston episode in a few weeks. But, it’s missing the state level organization. I think the state level is the hinge between national and local. One thing the show is getting at is Phyllis’s amazing network, which she had been building for years. She was active in the Republican Party. In 1967, she runs for and fails–basically, it was a rigged election–the National Federation of Republican Women. So all the women who are for Schlafly walk out, but she still has all those connections in every single state. So Phyllis is able to contact state leaders and the state leaders can contact the grassroots leaders. She’s able to turn the Equal Rights Amendment into a local issue, instead of it being all in Washington; she’s able to go in and talk to their congressmen, talk to their state representatives, in their local offices–which is so key–and say, “do you want girls on the local high school football team?” That is something that’s going to stick out for them in a way that talking about social security and things like that can feel so removed. But when you’re talking about, do you want your daughter in a fox hole, they make it such a localized argument, but it has this national implication. It’s hinging it all on the state level, like on a seesaw you have federal and local, and the state is like the pivot. I really see the state level as being so critical in this. Georgia was amazing, their organization: it never had a shot in Georgia. Sorry, Georgia. I’m fascinated by the strategy of it all. Morna used the word “manipulative,” which I think is one word. I always think of Phyllis as strategic, which I guess is the kinder version of manipulative [laughter]. But I am so fascinated by this organization. It’s mind-blowing when you get into it.

Shifting political identities and the woman who switched sides

Conn: When you said that the ERA never had a shot, another thing that I found interesting in your article is that you said it was surprising Georgia advocates for the ERA were never able to get it ratified in a time when Jimmy Carter was president, a majority of the Georgia legislature was democratic, and at a national level they were nominating many Republicans in favor of the ERA. So, when I think of this kind of identity cleavage–and I think a lot of the best scenes in the show are like when you see the two groups of women walking up the staircase, going down different political paths and looking across at each other, so powerful–I think in contemporary terms about our nationalized Republican and Democratic super identities. But, it seems like there was a different kind of cleavage here, where it seemed like it cut across Democratic and Republican lines in really interesting ways. Could we talk about the strange political affiliations? I’m interested in what this was like to live. This was what, an 8-10 year struggle in Georgia where neighbors, Republicans, and Democrats had this really strong disagreement that didn’t necessarily line up according to political parties. That sounds really intense and hard.

Gerrard: Yeah, you know Margaret Curtis was ostracized by her friends. She lived in a pretty conservative part of town. She lost a lot of her friends because she actually spoke up. She represented herself as a housewife for the ERA, so she wasn’t like, “I’m going to burn my bra” or anything like that. She still was herself, but it did affect her social life.

Harvel: In most of the oral histories I’ve listened to, people didn’t talk a ton about their personal lives. Margaret Curtis did a little bit. The biggest personal conflict that I remember from my research is the woman who switched sides halfway through.

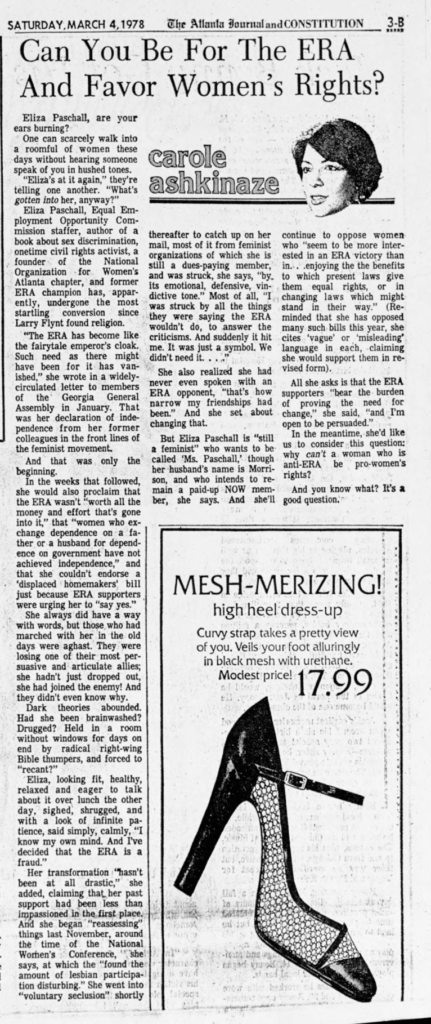

Morris: Oh, Eliza Paschall—-!!!

Harvel: Yes! She’s what first came to mind, Guy, when you were talking about the long battle for ratification and what that looks like. Having a woman who switched sides halfway through is quite interesting to me.

Morris: I love Eliza! I can talk about Eliza later, but let me get to the question. Right now we’re so polarized in our Republican and Democrat and then Democrats within their Biden or Bernie, but in the 70s there’s still a little bit of fluidity. Georgia and the south really just started coming out for national Republicans in 1964. Then George Wallace ran in ’68 and ’72, and he’s running outside of the party structure as the American Independent Party. So, this is the moment when the south is making its shift, so the lines of Democrat and Republican don’t necessarily mean what we think of them and weren’t as hardened. Even Phyllis Schlafly, in 1967 when she lost that National Federation of Republican Women election, walked out of the Republican Party. So she had this new flexibility to step outside of the party boundaries. She can challenge both parties and she can attract women who may not have been affiliated before. I think there’s this moment, especially in the south, but just sort of nationwide, where the parties are in flux. And gender hasn’t been talked about, sexuality hasn’t been talked about. Abortion, which I think comes across really well in the show, is that abortion is becoming something people are talking about more publicly and taking issues on. These things aren’t as hardened as we think of them now. A great example of this is at the very end of episode 3, the credits music is “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory” sung by Anita Bryant, who in 1972 sang at both conventions, at the Democratic and the Republican conventions which were both in Miami, which is where she was. So, they even had the same entertainment. I love that detail. They don’t let you know that, but I was the dork that was really excited to hear Anita Bryant singing at the end of the show.

I can talk about Eliza Paschall because I love her too! She’s a Scottie, Agnes Scott class of I wanna say ’36, she might have been 38, I’d have to look that up. She’s so amazing! She’d been a big Civil Rights activist: she headed the first office of the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission in Atlanta, and then she co-founded the National Organization for Women and was Atlanta’s “Feminist of the Year” in 1970 and co-founded NOW in the same year. In ’78 she changes her position. Her papers are at Emory and she has really amazing writing, because she’s an Agnes Scott graduate, about that she spent her life tearing down walls between black and white and she saw the feminist movement as trying to build them between men and women. My favorite thing she ever wrote is “Alice in Abzug Land” where the housewife Alice falls through a hole and enters this world where Bella Abzug is the Mad Hatter and it’s just a fantastic piece of writing. I think the next project I want work on, I’m gonna start this summer, is a collection of Eliza’s writing, because she’s got beautiful writing from the time she was an ambulance driver in World War II until she we went to work for the Ronald Reagan White House, she worked in the Office of Public Liaison.

Opposing the ERA in Georgia

Conn: After the first two episodes, I’m not sure what the show will focus on. But the A-list actor is playing Schlafly, and the focus of the first episode is more from the STOP ERA side. Samantha, our last conversation suggested that our research for our upcoming exhibit tends more to the pro-ERA side. I was wondering how seeing the perspective from Mrs. America, what you might have seen a little bit differently, what some of the frictions might have been, how you perceived Schlafly after your research, and how she’s going to be portrayed in our exhibit. What are some of the differences between our exhibit, which may show more of the pro-ERA activism versus the show, which focuses on the other side?

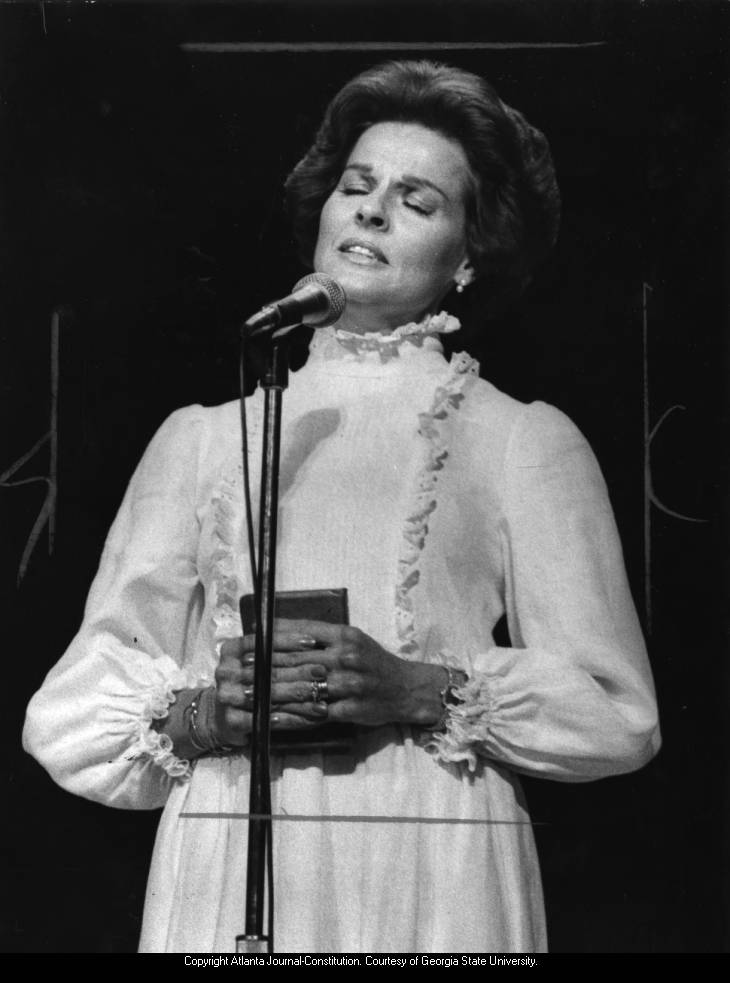

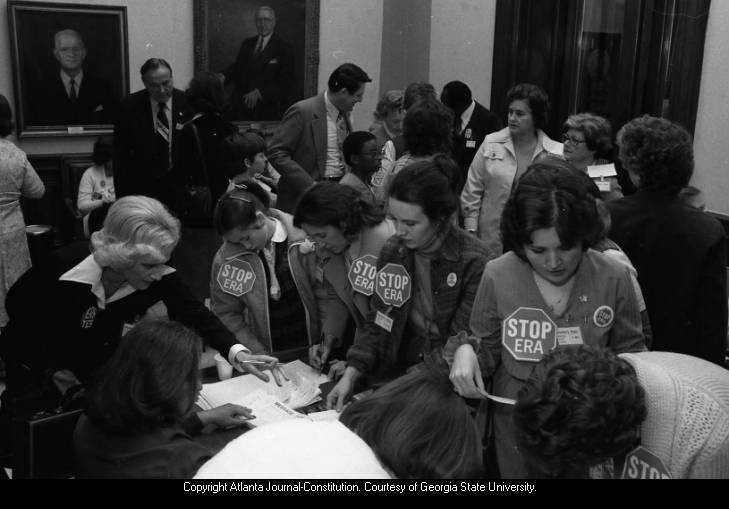

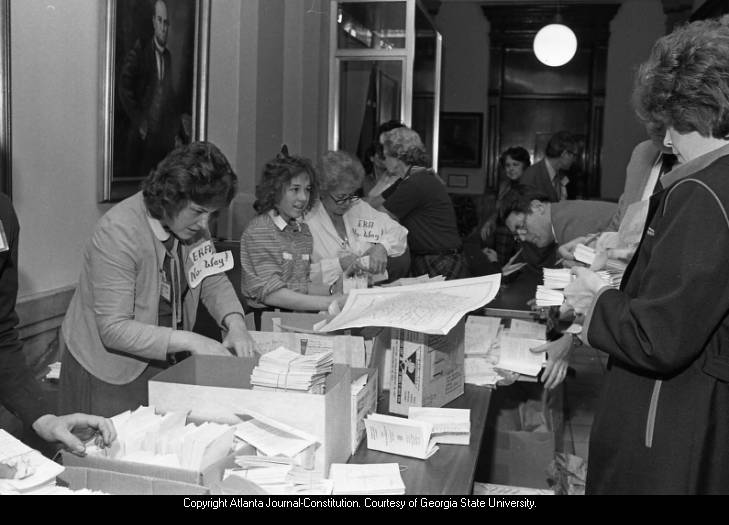

Harvel: Since the last time we talked, we’ve been including more anti-ERA perspective. There’s this wonderful oral history that was done by Jess Jones that presents the history from an anti-ERA perspective in Georgia. We’ve been trying really hard to include more of that narrative. The second panel of our exhibit addressed that anti-ERA movement, their tactics and their strategies. It was really interesting to see that reflected in the show, especially when they depict something we reference in the panels like an oral history I listened to of someone talking about how in the Georgia legislature the women would come and they would bring cookies and jam and all these things.

Opponents of the ERA writing messages to their congressmen during the Georgia Senate’s vote on the ratification for the ERA, Atlanta, Georgia, January 21, 1980.

Gerrard: With their blue hair and their curls.

Harvel: I also enjoyed how they showed that the women’s liberation movement really underestimated the power of the opposition. I think that was pretty common. I don’t know if that comes down to, they didn’t think anyone would want to oppose it or some educational elitism, “these women don’t have degrees,” “they’re not smart,” “they can’t do anything,” which is really interesting because it’s supposed to be the women’s liberation movement.

Morris: I think there was a lot of “those states are so backwards.”

Harvel: Later on I think they do scrounge up some evidence, they find some constitutional lawyer’s report about what the ERA will do.

Morris: It’s the Yale Law School journal that they dig up. That sucker circulated all over the STOP ERA. I think Schlafly’s greatest argument eventually–in the early episodes of the show she’s still figuring out the argument–but I think her greatest argument against the ERA was the uncertainty of it all. So she could make these claims, like: that means we’ll all be in the same bathroom, or girls will have to be on the football team, or women will be in the foxholes. Then her response can be, “well, prove me wrong.” So, did she tell a lie? I don’t know, we have gender neutral bathrooms now. A lot of her fears about the ERA have actually come forward. We have gay marriage, we have women in combat–they just aren’t getting combat pay, necessarily–but a lot of it has come true. I think the uncertainty of it all was her greatest weapon, because it was more like things may not be perfect now, but… What Eliza Paschall is really saying is change the laws you don’t like, but don’t give the federal government the blanket power because then you can’t control it anymore.

Gerrard: And they were not about big government.

Morris: Which is why I think it’s important that the movement came across as a local level, grassroots movement, instead of a top down, even though it’s a lot of Phyllis at the top. She was really empowering the grassroots. She retained control, definitely, but that was important to not be top down, for her. I think that was one of the other problems, even within Georgia, and Morna and Samantha might know more about this because you do have the ERA papers at GSU, but in an early meeting of Georgia women Mamie Taylor was saying that we know it’s gonna pass, we just want Georgia to be one of the first 38. But they were really focusing on Atlanta and weren’t going out even to the bigger cities of Macon and Savannah, they were really Atlanta based, whereas as soon as STOP ERA gets going they are in every town in Georgia.

Gerrard: They were so organized and that really came through when we were talking with Lee Miller. They were super on top of this. Beyond all that, the Republican party has a lot to thank these women for, because they were extremely effective at just doing everything for the Republican party. If I was going to war, I’d want these women managing my war efforts.

Harvel: I think you’re right, that it was very Atlanta based at the beginning. I think later they did try to expand. Margaret Curtis talks about how they’d hop in the car and they’d drive all over the place. They definitely had several meetings in Athens. Athens became a big hub. I remember talk of Macon a couple times. They would go all over the place down there, all the way down south. But they were a little slow on the uptake, not quite as efficient as the STOP ERA campaign.

Morris: By the time got they got out there there’s already a STOP ERA group.

Gerrard: Rural groups generally tended more conservative. Even if they’re not necessarily conservative, they still see these urban educated women as uppity. There is a divide. I think that it was probably easier for the anti-ERA people to make footholds in rural communities. They’re speaking a lot of the same language.