TV Show Mrs. America and 25 Years of Women’s Collections at GSU!

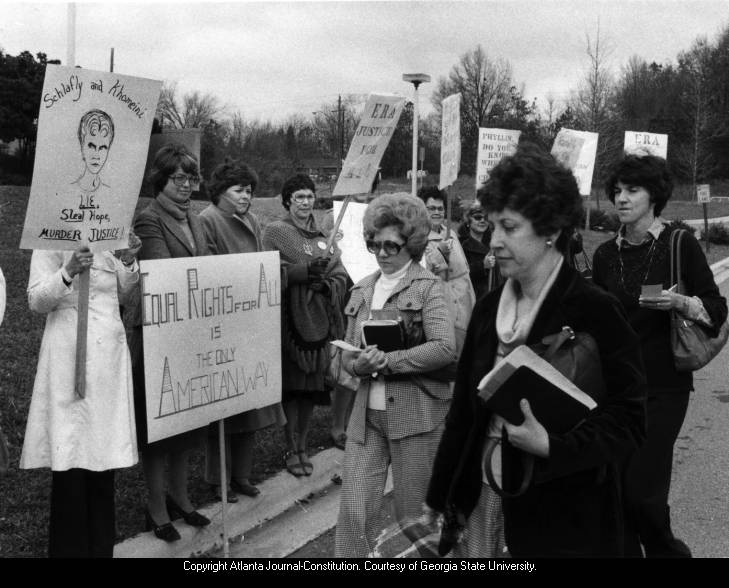

Pro-ERA demonstration outside Civic Center, Atlanta, Georgia, 1981 or 1982. The event is probably a STOP ERA Committee rally.

This April, we were scheduled to debut the exhibit ERA: Absolutely Yes in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Collections at GSU. While that exhibit and the opening panel discussion have been postponed, the history of the Equal Rights Amendment has been widely discussed in response to a new television show. Mrs. America depicts a variety of pro-ERA advocates and leaders of the feminist movement, such as Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Shirley Chisholm, juxtaposed with Phyllis Schlafly and the leaders of STOP ERA. Archivist Morna Gerrard and GSU graduate student Samantha Harvel, the curator of ERA: Absolutely Yes, recently talked with Robin Morris about Mrs. America and the fight over ERA ratification in Georgia. Morris is an associate professor of history at Agnes Scott College and author of the manuscript Goldwater Girls to Reagan Women (forthcoming from the University of Georgia Press) about women’s work building the New Right in Georgia from 1955 to 1982. The first part of this discussion between Gerrard, Harvel, and Morris (below) covers general impressions of the show, writing the history of women’s lives, Phyllis Schlafly’s motivations, the importance of print culture to the movements, and Morris’s meeting with Schlafly. The next two parts will cover the fight for ratification in Georgia through the lens of the show.

What’d you think of the show?

Morris: I’m really enjoying it; it’s exciting to see this story up there. I think the 70s haven’t gotten enough attention and now that we’re getting attention for this era and especially the women’s politics and how the women’s politics are messy, I think that’s really exciting!

Gerrard: I think it came through with the back and forth between Bella Abzug and Betty Friedan: it’s not easy, it’s not sweet and lovely and nice. They all had different egos and issues, and I think they captured that really well. I feel like they captured the essence of the 70s really well too, and the politics.

Morris: The music is great! The music is so good and the fashion is so good. I mean, for 70s fashion. I love how Tracey Ullman is portraying Betty Friedan’s arrogance. There’s a scene in the elevator where they say something about the movement and she says “I am the movement.” I love how they’re getting these personalities in there.

Harvel: I’m really enjoying it! I really like the fact that it’s both sides of the story. When I was watching the trailer I got the idea that it was only about Phyllis Schlafly, but I like that it’s about both sides of the story and the inside look at the personal lives, especially watching Schlafly trying to navigate her personal life while trying to do all this professional stuff, but not professionally. She’s clinging to this identity of being a housewife, but she’s out here doing all this stuff outside of the home: having meetings in Washington, going on interviews. I found that conflict in identity interesting.

Writing the history of women’s lives

Gerrard: Well, she had help at home, didn’t she?

Harvel: Yes, I thought that was interesting, too. I was like, are you really a homemaker? Are you the one making the home?

Morris: I think so many women had help at home.

Gerrard: Oh yeah, on both sides.

Morris: Yeah, on both sides of this. She doesn’t really talk about it often. This is something I come across in my work when I’m writing about conservative women: how much of the personal life do I put into it and how much do I keep. I was interviewing a woman, Lee Ague Miller, who Morna was with me for, and I asked her about how she was doing this balance. She just said, “I had help.” And I knew that was just the end, so ask the next question. But then I started thinking, with Schlafly and for so many women, no one is talking to Jerry Farwell and asking him, “so who’s raising your children?” or, “who’s throwing the ball with your son? Who’s raising your boys to be men?” That’s something that I’m always having to deal with, these expectations that we talk about women’s personal lives in a way that we don’t talk about men’s personal lives. That’s something that I’ve been struggling with as I write, the expectations of writing history and portraying the history of women’s lives.

Harvel: I think that’s a really good point! The reason Schlafly’s personal life is interesting to me is because she identifies as a housewife. If that wasn’t a part of her identity, it might not be as relevant. But as such an important part of where she’s coming from, it’s a really interesting factor.

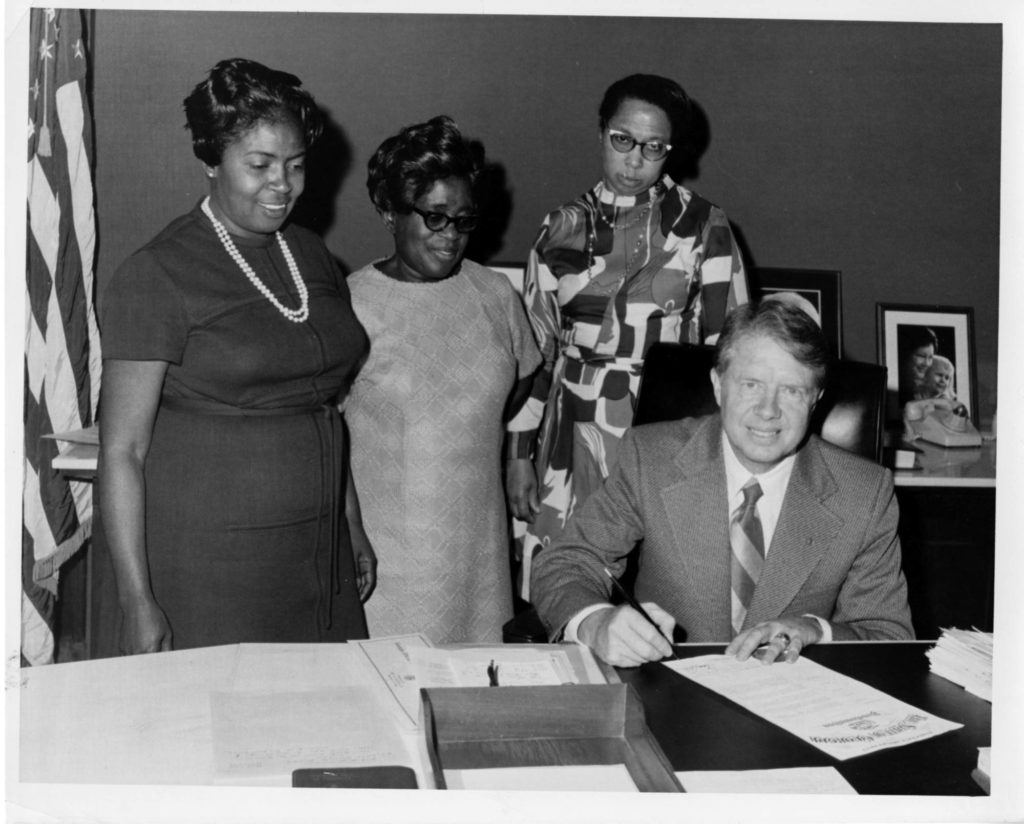

Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter signs a government proclamation establishing a “Maids Honor Day.” Standing behind Carter are National Domestic Workers Union founder Dorothy Bolden (left) and two other women.

Morris: Yeah, I need to keep forming how I think about this. I know it is part of what she says, but she’s also never shied away from these other identities she has. She does portray herself as a mother and as a housewife and talks about how women can do it all. I’ll keep thinking about this.

What motivated Schlafly?

Gerrard: I might be off base, I felt like she used this “I’m a housewife thing…” She was very manipulative, as far this portrayal of her is concerned. “I’m not going to make it being this serious person who can talk about SALT [Strategic Arms Limitation Talks] and about all of these important men’s issues. So this is how I can find my way to power or prominence, but going this route because this is what people will listen to me, if I talk about that.”

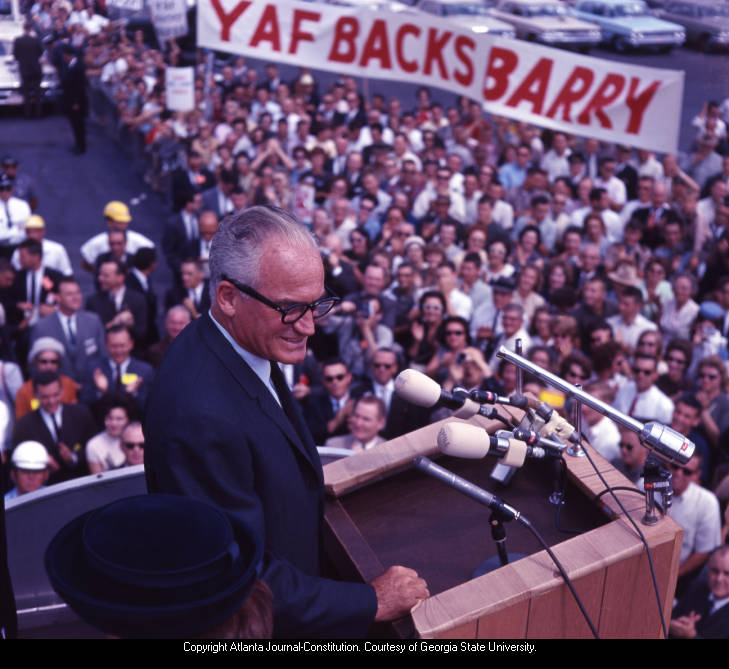

Morris: Yeah, definitely. I am so convinced that the reason she gets into the ERA battle at all is because the men would never listen to her talk about the things she really cared about, which were strategic defense, national defense, nuclear preparedness. She’d been involved in Republican politics since 1956 and its not until 1972 that she would start talking about women and gender. She had been such a voice on the right wing of the Republican party and kept getting dismissed. There’s a scene in the first episode where she meets with Barry Goldwater, which I really hated because Peter MacNeill looks nothing like Barry Goldwater, and I kept thinking who is this supposed to be? I think overall the women look great! But the men, I’m kind of like, who is that? Also, it shouldn’t have been Barry Goldwater it should have been Sam Ervin, but that gets nitpicky. If she had won either of her two other races for congress we would absolutely have an Equal Rights Amendment now. She would never have fought it and if she hadn’t been involved in it, it would have passed, probably by the end of 1973.

The importance of print culture

Harvel: I think they’re hitting the nail on the head about Schlafly’s attitude and her communication techniques. I really like that they’re showing how effective the newsletters were, how important those were. That’s going to be a part of the cases for the exhibit. I’m planning to feature how they used these newsletters and letters. I think that’s going to be really interesting for current college students, because people don’t think about how movements happened before the internet. What did you do before you could group text all of your friends to say, “Hey, let’s show up to this protest.” It all starts with The Phylis Schlafly Report, which we have couple different copies of in the archives. So that was really exciting to see. The one we’re using in the exhibit is from 1981, so a whole decade later than the one that they feature.

Morris: Her biographer, Carol Felsenthal, said that one issue, the February 1972 issue where she first mentions ERA, became a collector’s item for feminists, just like the first issue of Playboy. She’d been doing The Phyllis Schlafly Report since she left the National Federation of Republican Women in ’67/’68 and by 1971-2 she had 3,000 subscribers to it for $5 a year, so that’s pretty good income. By 1980, toward the end of the ERA battle, she was up to 35,000 subscribers. So this movement really does get her the national platform that she’d been trying to get. And the newsletter is so important. When you look at it, it’s cheap to produce because it’s just blue ink on white paper, but she didn’t have copyright on it. She would tell people “go mimeograph this.” So when you go to elected official’s papers they have The Phyllis Schlafly Report. The women are taking that to them. Women all over Georgia were using that. She gets her law degree, which I think they’re leading up to, she gets her law degree through this movement, but she’s not writing in esoteric legal language. She’s not making legal arguments, she’s making arguments that her followers will follow and repeat. That’s the language of the Report. She teaches one platform issue per issue of the newsletter, so she might have ERA, SALT treaty, Panama, ERA. That was another way for her, once people got hooked on her talking about the ERA, to still talk about national defense. She was never all ERA all the time. Later she gets into ERA and labor, ERA and abortion, ERA and homosexuality, how do we get out of Vietnam, things like that. She’s amazing, I have no idea how many hours were in Phyllis’s day.

Harvel: What did the woman say? “We don’t have to worry about the fringe?” Because Schlafly was the “fringe.”

Morris: Betty Friedan said I’ll never have to say that f-ing name again. Morna you might remember, was it Friedan’s son and Schlafly’s son that had the same advisor in graduate school?

Gerrard: I didn’t know that.

Morris: I think it was Friedan and Schlafly that had the same advisor in engineering or something, and they were like, “Let’s just not talk about our mothers.” I’ll have to look that one up.

Gerrard: A moment I find quite interesting, and really quite important today, is when she’s just finished her interview with Donahue and he points out that she may have been not telling the truth. She pivots in a way, so relevant today, where she doesn’t acknowledge that she didn’t tell the truth but she just redirects where it’s going. And it’s like, so this is where “fake news” got a really good start.

Harvel: I think its using the slippery slope argument. If we let them do this then they’re going to do all these things so that’s why I can say that the ERA does this.

Gerrard: Yeah, you don’t have evidence that you can use so opt for potential anecdotal arguments.

Harvel: Later on I think they do scrounge up some evidence; they found a constitutional lawyer’s report about what the ERA will do.

Morris: It’s the Yale law school journal that they dig up. That sucker circulated all over the STOP ERA. I think her greatest argument eventually, in the early episodes of the show she’s still figuring out the argument, but I think her greatest argument against the ERA was the uncertainty of it all. So she could make these claims, like, that means we’ll all be in the same bathroom, or girls will have to be on the football team, or women will be in the foxholes. Then her response can be “well, prove me wrong.” So, did she tell a lie? I don’t know, we have gender neutral bathrooms now. A lot of her fears about the ERA have actually come forward, we have gay marriage, we have women in combat–they just aren’t getting combat pay, necessarily–but a lot of it has come true. I think the uncertainty of it all was her greatest weapon, because it was more like things may not be perfect now, but…What Eliza Pascal is really saying is change the laws you don’t like, but don’t give the federal government the blanket power because then you can’t control it anymore [see part 2 of this interview for info on Pascal] . Phyllis eventually sends out a list to every state to say here’s who you need to speak: find a woman in labor, find an African American woman, find a Catholic woman, find a Jewish woman. So she’s working it, but she’s also not telling her members you can’t be in the White Citizens’ Counsel. The character of Alice, by Sarah Paulson is completely made up, by the way. I don’t know what’s happening there.

Harvel: She’s just meant to act as an embodiment of Phyllis’s inspiration.

Morris: She lets us see how Phyllis is thinking and operating. Otherwise we couldn’t see inside of her head as much as we do.

Gerrard: There are moment though when she looks at the camera, and it’s just like this is what’s going on, I got this. That’s done so well!

Morris: Cate Blanchett is doing it so it well. Phyllis was always under control. She did not lose her cool. I love watching clips of her where Betty Friedan, you can just see that Betty Friedan loses her cool and Phyllis could just look at the camera and smile [laughter]. I saw her speak a couple of times and I think the worst thing you could do if you ever fought Phyllis Schlafly, the greatest protest you could have against her, would be to sit there and listen respectfully and not do anything. As soon as someone got up, I was at one at the Yale Law School where she spoke, and this woman got up and stormed out of the room and slams the door and Phyllis just stops while the woman has a temper tantrum, looked at us, and kept going. She knew, she was at that point like 85 and its like “I still got it.” She loved getting to that point where she could just incite people and she could be the calm, cool, collected one. It’s amazing.

Gerrard: It’s a skill.

Morris: I know, I don’t have that. Sometimes I try.

Phyllis Schlafly speaking out against the ERA at a Mothers on the March event, Atlanta, Georgia, October 11, 1980.

Meeting Schlafly

Gerrard: Can you tell us about reaching out to her to ask her to be interviewed?

Morris: Yeah, I interviewed her in 2009. I don’t remember how I initially reached out, I guess a simple letter or email. I had looked at the papers of STOP ERA at Emory and I had talked to the co-chairman–STOP ERA leaders called themselves chairmen–I had interviewed her. So I asked for an interview, she said no; she reached out to Lee Wysong to see if I was okay [more on Wysong in part 2]. I went to the Eagle Forum meeting, just to meet people and get in that network. Then I got to go to her office in St. Louis. I was really fortunate because her secretary, who had the fabulous name of Deb Pentecost–best name ever!–she and Phyllis allowed me to look in her archives. At one point she was like: well, I can’t let you in, but I can just make copies. So, I was like okay, can you copy these four boxes. And she said yeah, it’ll be $200. So I have a copy of the papers. It was amazing! Phyllis was really generous with me. Meeting with her, though, she’s so well rehearsed that I couldn’t really crack that. I didn’t get answers that other interviewers haven’t gotten. I think the grassroots interviews that I did were much more useful for getting to that and looking at papers. But it was a real honor and also really scary. She’s intimidating. I think she would’ve flipped out at the sex scene, which I think was egregious and unnecessary: no one needs to see a Phyllis Schlafly sex scene. But I think she was really concerned toward the end of her life with being a part of the story, that she didn’t want to be erased. So I think she would probably be speaking out against it, but she would also be flattered and excited to be included in the story.

Gerrard: She’d be loving it.

Morris: Yeah, she’d be loving it, but publicly hating it, I think. The story of conservatism is always Goldwater to Reagan. It’s always men. The story of the women’s movement is always Gloria Steinem and Bella Abzug. I think she would be excited that she’s complicating this. She’s making everything messy, which she loved.