A Young Man of Conviction – The Early Years of M.H. Ross

The M. H. Ross Papers digital collection is now publicly accessible online. Digitization of the M. H. Ross Papers is being funded by a $48,865 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and will continue through September 2018.

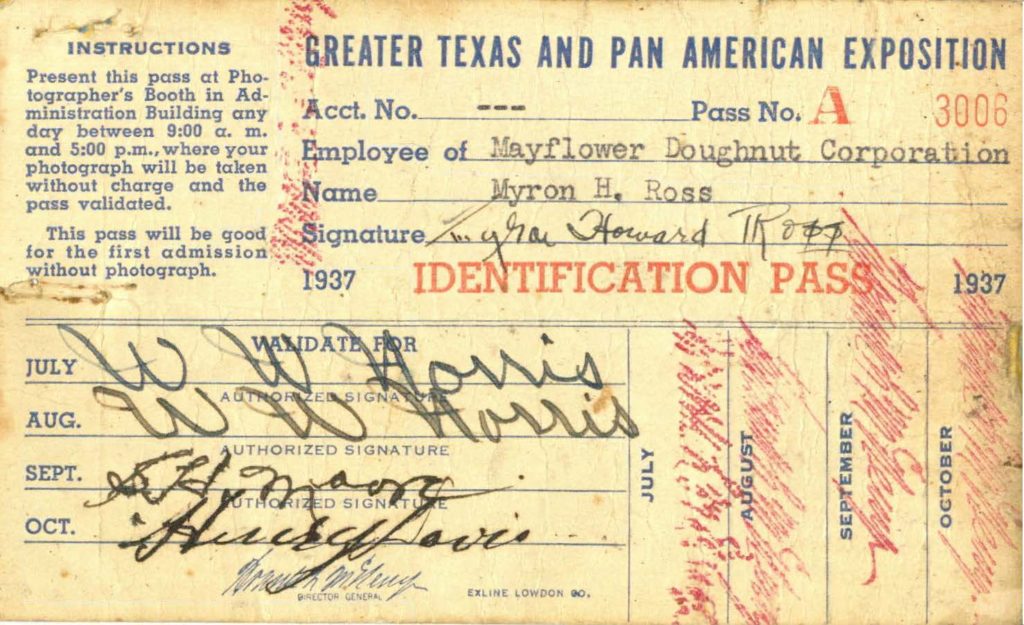

At the age of 18, Mike dropped out of the City College of New York and traveled to Dallas, where he worked a summer job for the Mayflower Doughnut Corporation as part of the Greater Texas & Pan-American Exposition. He worked long hours operating the doughnut making machine but, with his meager earnings and some free food from his job, he was able to make ends meet.

“As you ramble on through life, brother,

Whatever be your goal,

Keep your eye upon the doughnut,

And not upon the hole. “

[L2001-05_004_13]

By early 1938, Ross had moved to Chickasha, Oklahoma, where he operated a water-fired boiler for an egg processing plant. It was here that he got his first taste of labor organizing—and lost his job as a result. Much to his surprise, a simple letter to a newly formed union chapter about possibly organizing some coworkers granted him a personal visit at his boarding house from David Fowler, district president of the United Mine Workers and the director of the Oklahoma-Arkansas chapter of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Fowler explained some basics of union organizing to Ross, gave him cards for the men to sign, and said that the union would petition for National Labor Relations Board elections on their behalf. It was a whirlwind for Mike Ross but, before he could move forward on anything, word had spread of his intentions and he found himself unemployed.

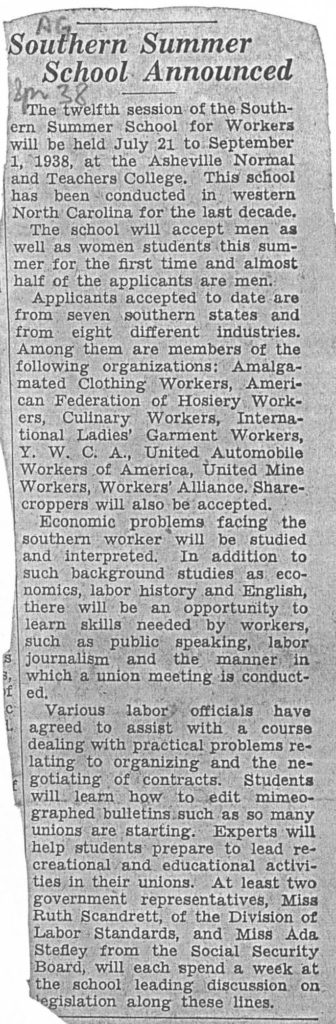

Ross returned to Dallas to work on the chicken farm of a friend for room and board and continued to attend various local social meetings. He was not to stay long, however, as he soon received a full scholarship to attend the Southern Summer School for Workers in Asheville, North Carolina.

Over the course of six weeks in the summer of 1938, Mike took classes on everything from history and economics to writing leaflets and how to conduct union meetings. He was exposed to laborers and educators of various backgrounds from around the country who shared his vision of economic fairness and civil rights. Despite his young age, he was such an enthusiastic student that in 1939 he was asked to return to the school as a staff member.

In November of 1938, Mike Ross and several others traveled by car to Birmingham, Alabama to attend the first Southern Conference for Human Welfare. The purpose of this inaugural meeting was to gather support for New Deal reforms and to discuss economic and social conditions in the South. This meeting of over 1,000 delegates included U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, Alabama Governor Bibb Graves, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Eleanor Roosevelt. On the second day of the Conference, the Birmingham police, led by Eugene “Bull” Connor, attempted to segregate the audience. According to Ross, Mrs. Roosevelt placed herself in the middle of the room in protest.

In 1940, Ross landed a grant-funded position of $25 a week with the Labor’s Non-Partisan League in North Carolina, becoming the youngest political organizer to be hired by John L. Lewis, a labor leader whose oratory skills Mike greatly admired.

Mike’s first steady job was to encourage laborers to run for political office in their respective communities and he found great success in this and other arenas. In fact, his success in appealing to working people was so great, and his convictions so strong, that he would soon be sent to some of the most dangerous situations in the South as an organizer, at tremendous risk to his own safety and the safety of his young family.

To learn more about Mike Ross’ early life in the M.H. Ross Papers, explore these related folders:

Labor organization – articles, speeches, flyers, and notes, 1937-1939, undated

Summer School for Workers – songs, articles, programs, 1938-1943

Labor school articles, 1938-1939, undated

Labor Flyers – locals, Summer School for Workers, 1938-1939, 1941, undated

MH Ross, Interviewed by Jane Ross Davis (Tape 1 of 6)

MH Ross, Interviewed by Jane Ross Davis (Tape 2 of 6)

MH Ross, Interviewed by Jane Ross Davis (Tape 3 of 6)