Making HERstory: Admission of Women to the Evening School of Commerce

Georgia State traces its origins to day and nighttime commerce classes on the all-male Georgia Tech campus. The night classes attracted older students seeking continuing education opportunities to enhance their established careers in downtown Atlanta businesses. By 1914 a number of evening school classes moved downtown to better serve these young men, and this location became Georgia State. When the first Tech commerce students graduated in 1916 with Bachelor of Commercial Science (B.C.S.) degrees, all seven had full-time jobs.

At the time, male and female students in Georgia’s public colleges were educated separately. Women had worked for admission to the University of Georgia (UGA) since the 1890s, but it wasn’t until 1916 that the state legislature approved co-education at UGA—in graduate programs only.[1] Elsewhere in the nation, advocates in the women’s rights and suffragist movements were making more substantial progress toward coeducation in public schools.[2]

In September 1917, though, five months after the U.S. entered World War I, Tech Dean Wayne Kell made a surprising step forward by admitting thirty “coeds” among the 158 new undergraduate students at the downtown location.[3] In doing so, he ensured the continued growth of the commerce school while male students went to war.[4]

Among the female undergraduate students was the 51-year-old principal of Atlanta’s Commercial High School, Annie Teitelbaum Wise.[5] Wise had opposed coeducation in her school (1915), but she was overruled and ended up as principal of Atlanta’s first coed high school.[6] Wise became the first female graduate of Tech (and Georgia State) when she earned her B.C.S. degree on June 16, 1919.[7] The peace treaty ending World War I was signed that same month.

After completing her degree, Mrs. Wise became a part-time instructor in commerce—and the first female faculty member at Tech (and Georgia State).[8] She continued teaching during the Fall 1919 school year when, with returning veterans, downtown Evening School enrollment doubled to 310.[9] In addition to her duties as a high school principal, she also joined the Atlanta Public School Teachers Association, which, under her leadership, became Local 89 of the American Federation of Teachers.[10]

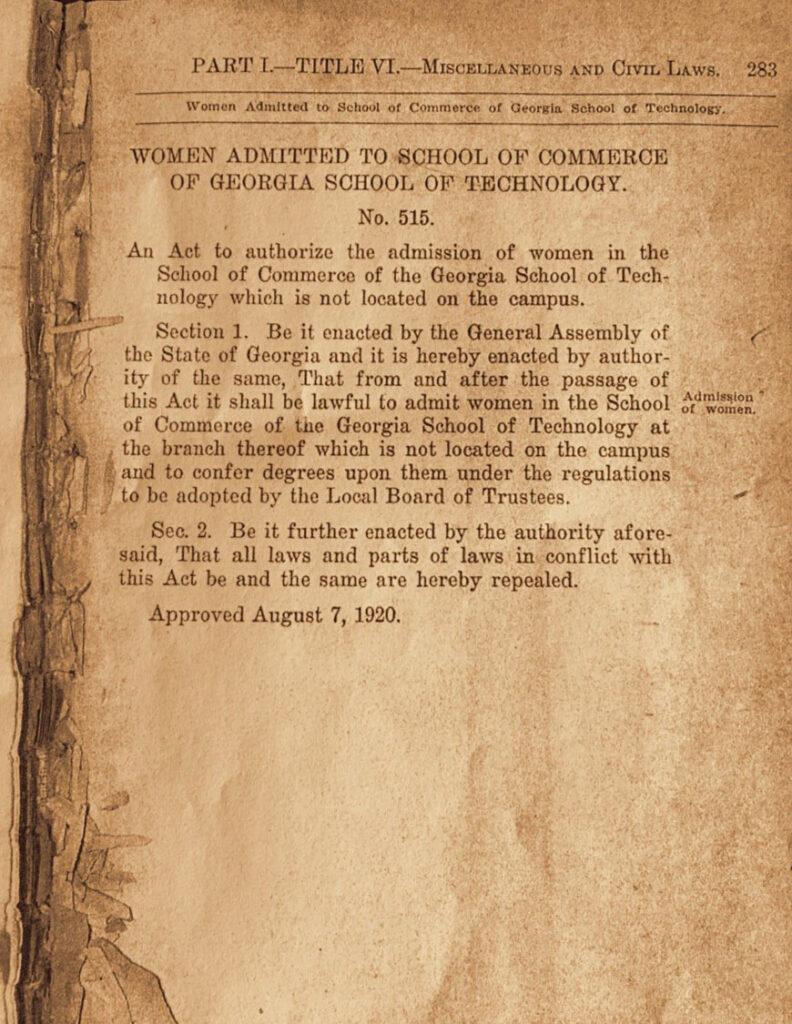

On August 7, 1920—more than a year after Wise’s graduation—the Georgia legislature passed a law authorizing women to attend the Tech School of Commerce—but only at the downtown location (i.e., Georgia State).[11] This legislation was enacted eleven days prior to the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving women the right to vote. At the downtown commerce school, the percentage of women in the freshman class varied throughout the 1920s but significantly exceeded female commerce undergraduates elsewhere in the Southeast.[12]

Board of Regents approval for co-education on Tech’s campus—but only for work not offered by other senior University System of Georgia institutions—was passed in 1952.[13] Tech did not employ another female faculty member until 1960.[14]

The disruption caused by the first world war created circumstances that allowed Dean Kell to make significant, progressive changes at evening classes in the downtown Atlanta business district: he not only admitted undergraduate women, but he made it possible for his successor to hire a female instructor. While his decisions may have also helped the war effort, these changes were not permitted at more visible, established schools with younger students, like Tech. Kell’s opportunities to make changes were strengthened by Mrs. Wise, an older woman determined to enhance her educational credentials. After the war, the state legislature reaffirmed the old all-male status quo on the Georgia Tech campus, but it also legitimized co-education at the downtown Atlanta classes (Georgia State) and allowed it to continue. By welcoming diversity so early in its existence, Georgia State made a firm step in a direction that now defines it among institutions of higher education.

Acts and Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, 7 August 1920

[1] Merl E. Reed, Educating the Urban New South: Atlanta and the Rise of Georgia State University, 1913-1969. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009, pp. 7-8. Thomas G. Dyer, The University of Georgia: A Bicentennial History, 1785-1985. Athens, [Ga.]: University of Georgia Press, 1985, pp. 170-172.

[2] Amy Thompson McCandless. “Maintaining the Spirit and Tone of Robust Manliness: The Battle against Coeducation at Southern Colleges and Universities, 1890-1940. NWSA Journal (Spring 1990), pp. 199-216. Johns Hopkins University Press. www.jstor.org/stable/4316017

[3] Reed, Educating the Urban New South, p. 7-8. Robert C. McMath, Jr., Ronald H. Bayor, James E. Brittain, Lawrence Foster, August W. Giebelhaus, Germaine M. Reed. Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech, 1885-1985. Athens, [Ga.]: University of Georgia Press, 1985, p. 124.

[4] One study downplays the influence of world wars and economic downturns on the switch to co-education. See Claudia Golden and Lawrence F. Katz. “Putting the ‘Co’ in Education: Timing, Reasons, and Consequences of College Coeducation from 1835 to the Present. Journal of Human Capital, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Winter 2011), pp. 377-417. They do say, however, that the preferences of college presidents have an influence (p. 403), that commuter schools make a seamless transition to coeducation (p. 405), and that schools that switch earlier to coeducation experience faster growth later (pp. 406-407). Another article emphasizes the role of the 1918 influenza pandemic, which, in combination with World War I, led to a shortage of labor that gave women an opportunity to gain rights they didn’t have previously. See Christine Crudo Blackburn, Gerald W. Parker, and Morten Wendelbo. https://theconversation.com/how-the-devastating-1918-flu-pandemic-helped-advance-us-womens-rights-91045 March 1, 2018.

[5] While Wise’s educational accomplishments and career were memorable, her biographical information (and age) are somewhat elusive. The fullest account of her life and career appears in Arlene G. Rotter, “Climbing the Crystal Stair: Annie T. Wise’s Success as an Immigrant in Atlanta’s Public School System (1872-1925),” in Southern Jewish History: Journal of the Southern Jewish Historical Society, Volume 4, Issue 2001, pp. 45-70. The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Atlanta, Ga., in Proquest Historical Newspapers, is particularly helpful since Wise frequently appeared on page 1: see 13 May 1929; 14 June 1918; 19 June 1915; 3 July 1915; 9 July 1915.

Briefly, Wise was born in Esperies, Hungary, on March 26, 1866, to Maurice and Mary Pollak Teitlebaum. She came to Atlanta in 1871, entered Walker Street School in 1872, and graduated from Girls’ High School in 1884. After initially teaching in the school system, she began her administrative career at Girls’ High School in 1892. By 1891 she had married Sam Wise, and they had a son, Leonard. Annie became the principal of English Commercial High School in 1910 when the business education section of Girls’ High was split off as a separate school. When the boys and girls commercial education programs were merged in 1915 to form Commercial High School, Wise was appointed principal at that school (in spite of her opposition to co-education). She resigned her position in 1926 due to ill health and died at her sister’s home in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 13, 1929.

[6] Rotter, “Climbing the Crystal Stair,” p. 57. The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984), Atlanta, Ga., in Proquest Historical Newspapers, 19 June 1915, p. 1 and 3 July 1915, p. 1.

[7] Reed, Educating the Urban New South, p. 8. McMath, Engineering the New South, p. 124.

[8] McMath, Engineering the New South, p. 124.

[9] Reed, Educating the Urban New South, p. 8.

[10] Atlanta Education Association Records, 1905-1971 (L1975-31), Southern Labor Archives, Georgia State University Library. Rotter, “Climbing the Crystal Stair,” pp. 59-62.

[11] Acts and Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, No. 515: “Women Admitted to School of Commerce of Georgia School of Technology,” Approved August 7, 1920. In Part I, Title VI, Miscellaneous and Civil Laws, p. 283. Reed, Educating the Urban New South, p. 11. McMath, Engineering the New South, p. 124.

[12] Reed, Educating the Urban New South, p. 12.

[13] University System of Georgia Annual Report, July 1, 1951-June 30, 1952, p. 41. McMath, Engineering the New South, pp. 270-275.

[14] McMath, Engineering the New South, p. 124.