The Gift of Activism: Which Side Are You On?

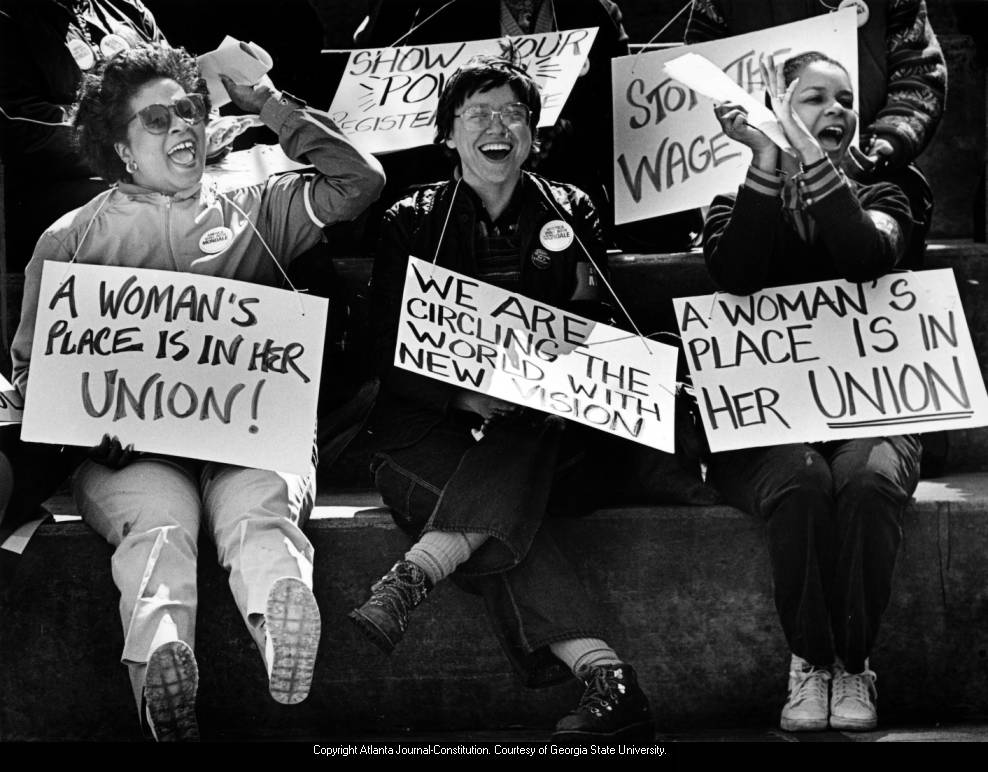

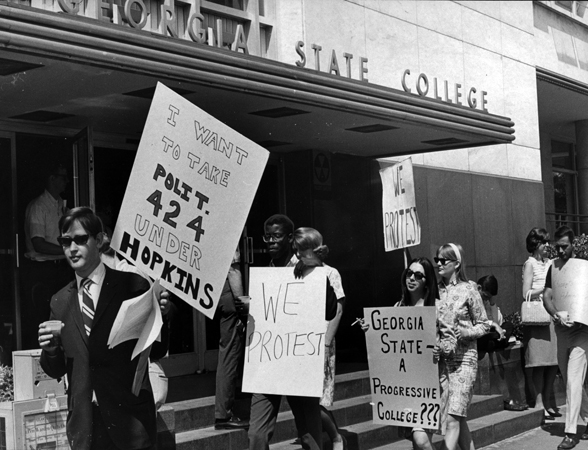

Every October, archives and repositories across the country celebrate Archives Month in order to showcase their collections and raise awareness of their work. In Georgia, the theme for this year’s Archives Month is, The Gift From One Generation To the Next. Georgia State University Library’s Special Collections and Archives Department uses the theme to create an exhibit of photographs and artifacts entitled, The Gift of Activism: Which Side Are You On?

Every October, archives and repositories across the country celebrate Archives Month in order to showcase their collections and raise awareness of their work. In Georgia, the theme for this year’s Archives Month is, The Gift From One Generation To the Next. Georgia State University Library’s Special Collections and Archives Department uses the theme to create an exhibit of photographs and artifacts entitled, The Gift of Activism: Which Side Are You On?

The struggle for rights, autonomy, and certain freedoms has been waged throughout human existence, and the gift of activism has been handed down from one generation to the next. Activism is defined as, “the policy or action of using vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change.” Dr. Martin Luther King inherited the legacy from Gandhi, who used such activist tactics to help end segregation.

throughout human existence, and the gift of activism has been handed down from one generation to the next. Activism is defined as, “the policy or action of using vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change.” Dr. Martin Luther King inherited the legacy from Gandhi, who used such activist tactics to help end segregation.

Archives are repositories of primary resources. Georgia State University Library’s Special Collections and Archives are filled with information documenting individual and grass roots activism, from correspondence to protest signs. Firsthand accounts in GSU’s oral history collections serve to record activists’ times of “vigorous campaigning.” [This exhibit is on the 8th floor of library south, Special Collections and Archives].

Come and Eat Your Lunch!

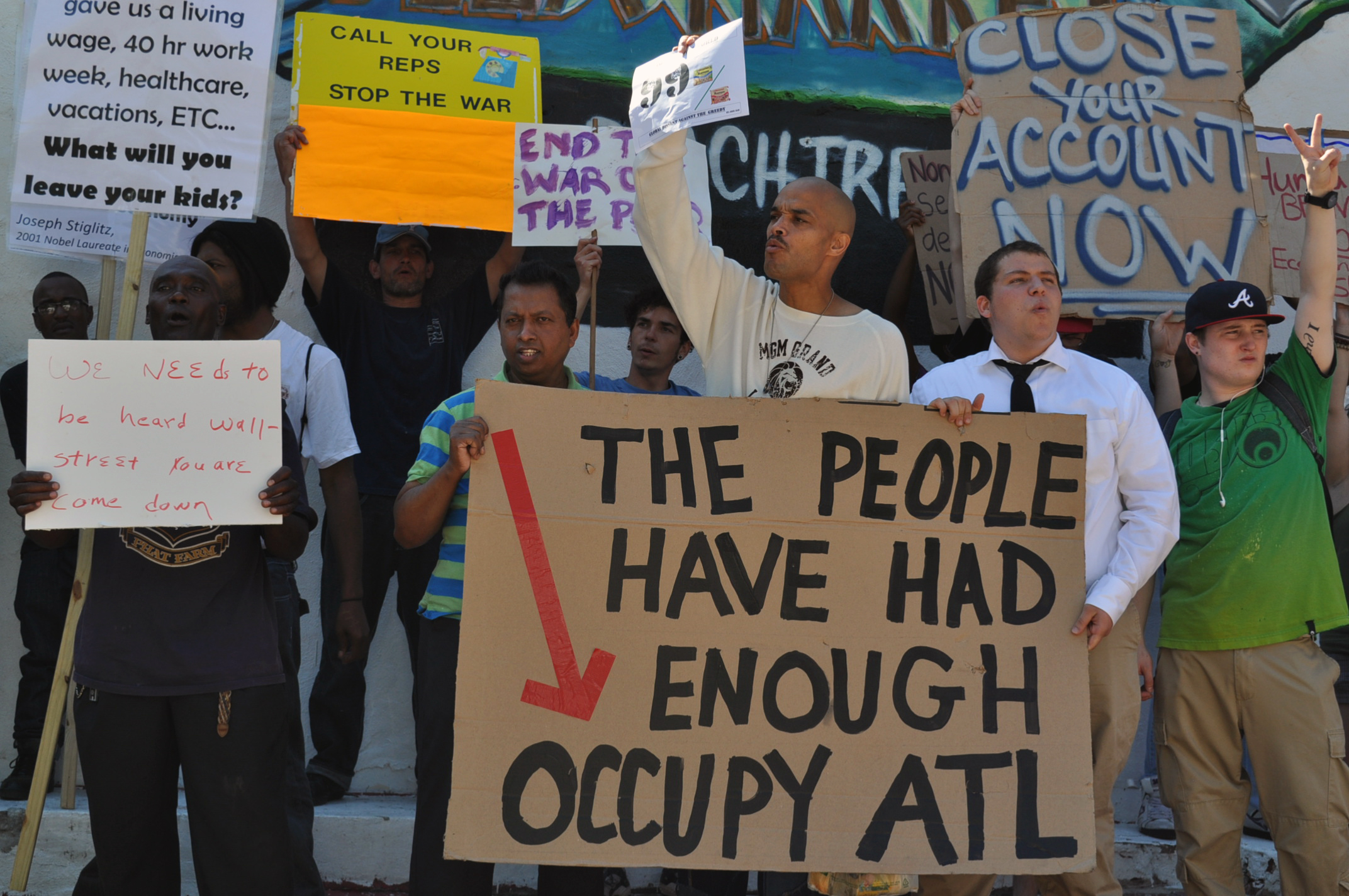

October 16th at noon: Diana Eidson gives a brown bag lecture, “Using Affective Discourse in Social Movements: Case Studies from Operation Dixie and Occupy Wall Street.” [Library South, eighth floor, in the Colloquium Room].

Diana is the Assistant Director of Lower Division Studies and a Ph.D. Candidate in Rhetoric and Composition. Diana Eidson explores Florence Reece’s famous 1931 labor song for Harlan County mine workers and the implications it has on today’s economic and social climate. Reese, the singer, asks, “Which side are you on, boys? Which side are you on?” This anthem has recently been appropriated by protestors involved in the recent movement, Occupy Wall Street. Faced with the deepest economic recession and worker alienation since the Great Depression, Eidson asks, what can scholars and teachers of social movements and public argument learn from the past? What might a rhetorical history teach us about civic literacy, about debate in the public sphere, about collective action for social change?