Part III: Mrs. America, Schlafly’s Georgia Lieutenant, and the Fight for Housewives

“So what’s interesting is that I got elected as a mom — motherhood and apple pie. [Then I] came down to the legislature and before I knew it, I was Cathey Steinem! I wasn’t Cathey Steinberg, I was Cathey Steinem. Because that’s when all they knew about the Women’s Movement — that my colleagues were Gloria Steinem and Bella Abzug.” –GA Legislator Cathey W. Steinberg

This April, we were scheduled to debut the exhibit ERA: Absolutely Yes in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Collections at Georgia State. While postponement of the exhibit and panel discussion has happened, conversation on the history of the Equal Rights Amendment builds in response to a new television show, Mrs. America. Archivist Morna Gerrard and exhibit curator Samantha Harvel recently had a conversation with historian Robin Morris about the struggle over ERA ratification in Georgia. The first part of this interview covered general impressions of the show, writing the history of women’s lives, Phyllis Schlafly’s motivations, the importance of print culture to the movements, and Morris’s meeting with Schlafly. In the second post, we discuss the importance of state politics as a hinge between grassroots and national movements, shifting political identities in the 1970s, the woman who switched sides, and the formidable organization of STOP ERA forces in Georgia. This third and final part of the discussion covers Schlafly’s Gerogia lietenant , the fight for homemakers and religious women, Shirley Chisholm and race in the ERA movements, and some concluding thoughts about seeing this history and pieces from the archives brought to life on the screen.

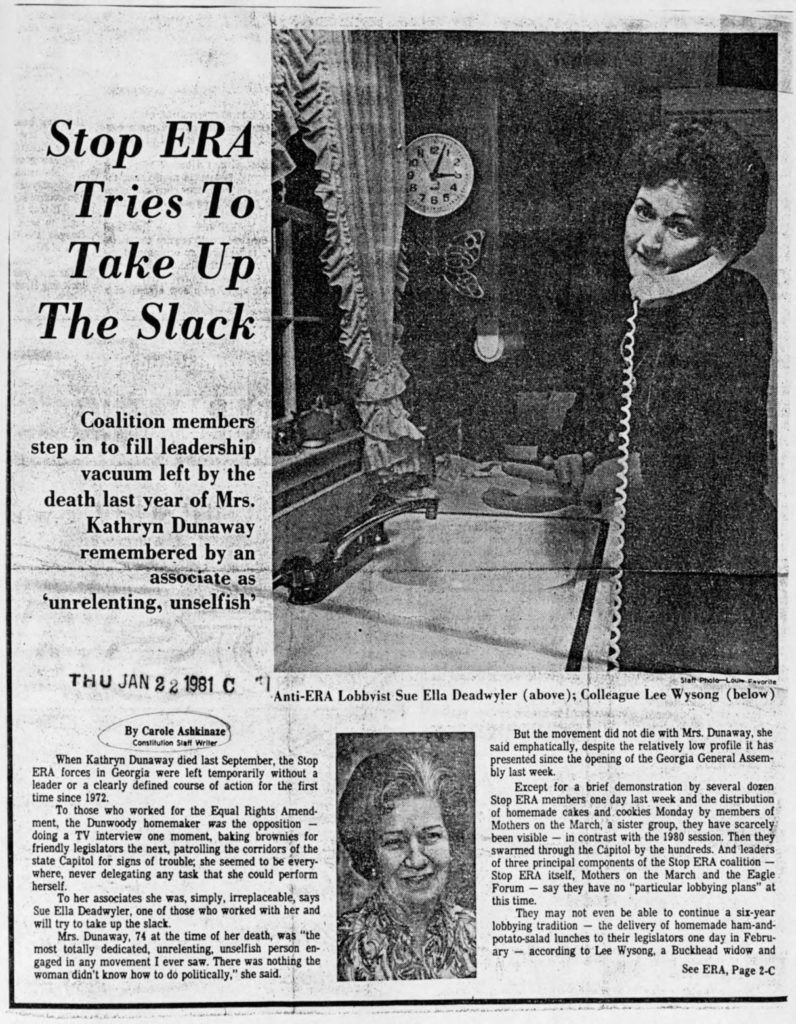

Schlafly’s Georgia Lieutenant

Morris: The STOP ERA leader in Georgia was Kathryn Dunaway and she was always a little self conscious that she didn’t have a college degree. She had a high school diploma and the number two leader was Lee Wysong who I think had an associate degree or secretarial school degree. She did work, she worked at her husband’s, her husband owned a business. They weren’t lawyers. Kathryn Dunaway’s husband was a lawyer and a former legislature. One thing I wanted to say, because Morna and I have met and talked to Lee Miller, she said briefly, in an interview, that she never supported the ERA. I found in the Nixon Library that she did. Lee Miller, at this point, was not big in ERA. It was more like if you deliver us busing, then I’ll deliver Georgia ERA. She was trying to work a deal. Lee Miller, at this time, was in Columbus, Georgia leading a National Republican Women’s campaign against busing. So she’s not involved in the ERA at all.

Conn: By against busing, you mean?

Morris: Against busing for the purpose of integration. Or just against forced busing.

Making the case to homemakers and religious women

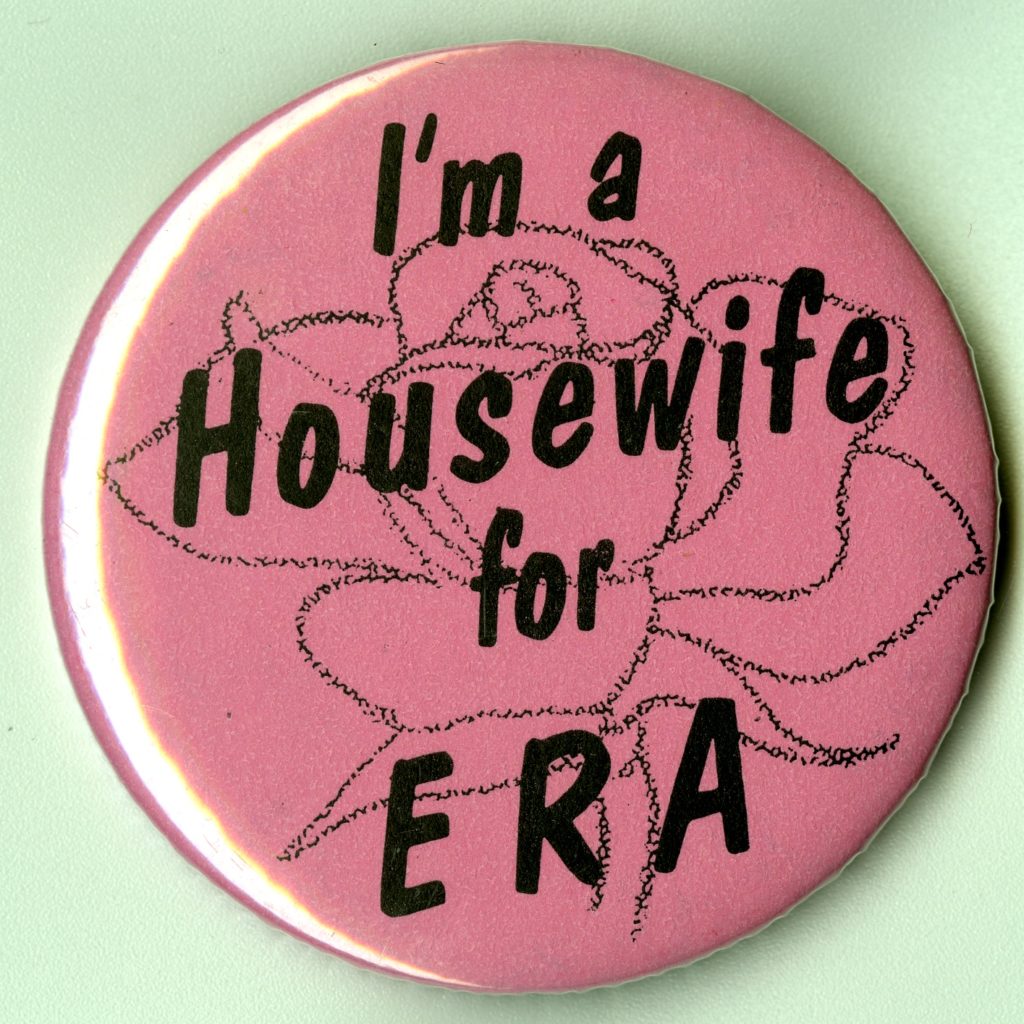

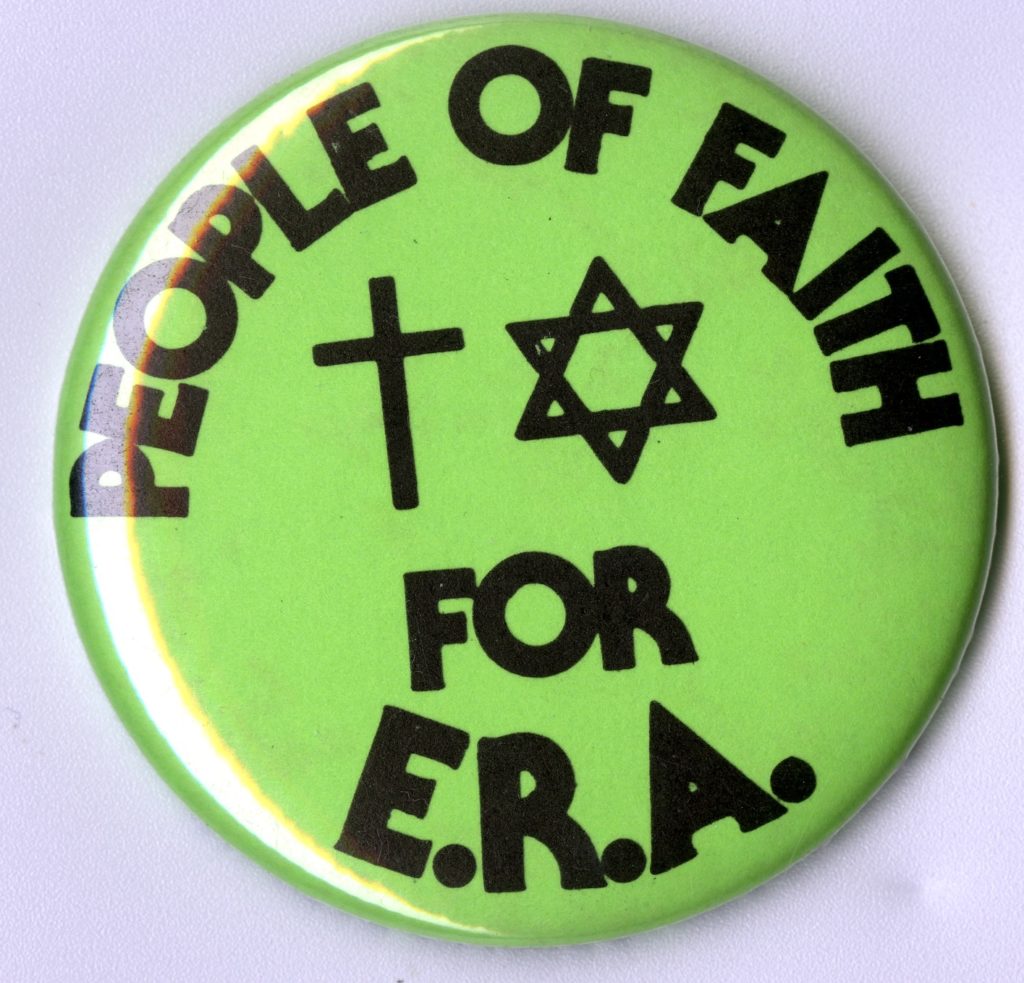

Conn: Samantha, when we talked last time you said one of the things you were most interested in was finding groups like Housewives for the ERA and Christians for the ERA. I’m assuming this was in a later stage of ratification. At that point, had the language been firmly coopted and just about responding to language Schlafly articulated? Where it’s housewives vs the coastal elite. Were those the terms the debate started with or were there other terms that we haven’t seen in the early episodes Mrs. America that we’re going to see in our ERA exhibit? What was the positive message in favor of the ERA?

Harvel: What do you mean by terms? As in “housewife,” “Christian?”

Conn: Right, in trying to make the local push for Georgia women, “women” wasn’t enough of to appeal to since that identity was being fractured. So did it come down to using Schlafly’s terms, like you work in the home so who gets to speak for homemakers? You’re religious so who gets to speak for religious women. Or was there a separate line of discourse going on?

Harvel: I think that brings up where some fraction occurs in the pro ERA movement. I think the rhetoric of I’m a housewife for the ERA, I’m a Catholic for the ERA, I think that comes from the pro ERA movement, in Georgia especially, really trying to not come off as a threat. In the show, Schlafly was talking about how the women’s liberation movement was godless, and the’yre not even married because no one wants them. I think a lot of conservatives in Georgia were really scared of feminists and of the women’s liberation movement. The housewives in ERA was really making a concerted effort to communicate that “we’re not trying to do away with housewives,” “we love housewives!” Or that it’s not against God to go for the ERA. I think those were really important arguments to make in Georgia. I’d be really interested to find out if organizations like that extended out into different states. But you also have in Georgia’s pro ERA movement, more similar to what we have seen in the show of women’s liberation movement, advocates for abortion, not necessarily religious, not married, or divorced, or lesbian. So you have these two conflicting sides showing up in Georgia and trying to work together for the same cause.

Gerrard: During the time the pro-ERA folks were travelling the state of Georgia to encourage people to get on their side, it tended to be Cathy Steinberg and Joyce Parker would go together. Cathy was the primary sponsor at that point, she’s also a Yankee with a strong Jewish accent, a very attractive woman, definitely that sort of northern, liberal physicality. Joyce was this little church lady, very pretty, delicate little church lady who talked the same language. They went on a lot of trips together because Joyce softened the message and would be able to get across to the more conservative folks. Cathy had the legislative knowledge to go along with her.

Harvel: Margaret Curtis talked about how she purposely wore her cross all the time to indicate that she wasn’t one of those godless liberals and I believe in women’s liberation.

Morris: I think they had to be so purposeful about their portrayal because they were also fighting this national portrayal. Whether it was accurate or not, there did get to be this sort of crazy, unshaven, bra burning, throw your children in a day care commune Bolshevik nursery stereotype. Yeah, I think housewives had a problem. There was a scene where Schlafly’s in a meeting and she read a part of The Feminine Mystique where Betty Friedan used language that compared marriage to slavery.

Harvel: The concentration camp?

Morris: Yeah, it was the the concentration camp. This is only 25 years after the end of World War II, when she wrote it was only 18 years after the end of WW II, so as much as we think that’s charged language it was amazing at that point. And then there’s women like Kathryn Dunaway, who have aspired to get to that class where she could stay home with her children. She had worked while her husband went to law school, her family had lost money in the depression, that’s why she couldn’t go to college. So she aspired to this level of society, this social class where she could stay home with her children. She’s having grandchildren but now she’s feeling her legacy attacked by language like that. This whole language that pro-ERA women were trying to say were really this liberation, was counter to what other women saw: that being a housewife had liberated them from the working class jobs that Betty Friedan was never going to have. It’s really critical for Housewives for ERA when Judy Carter, the first daughter in law, comes out in that group. Rosalind does a little bit, but especially Judy is important for spreading that message and this message of a domestic feminism, feminist domesticity.

Harvel: What you’ve been saying reminded me of in the show what Gloria Steinem said, that “someone always gets left behind in a revolution” or something like that.

Gerrard: I thought that was a very important conversation they were having at that point. That was part of a much bigger problem with losing a lot of your potential supporters. There was always that discussion of, well if you’re pro-choice you’ve got to be pro-choice for people to have 15 babies if they want to have 15 babies. You should be pro-everyone. That was a real problem within the feminist movement.

Harvel: One of the women in the meeting said something along those lines, that “we’re all about women’s right to choice, if she wants to choose…” She was saying that, but there was this tone condescension that I think is really prevalent, where it’s like “yeah, you can choose that, if you want, but that’s kind of sad.”

Conn: In Mrs America they said “We don’t want housewives thinking we’re against them.” To which somebody replied “We are against them.”

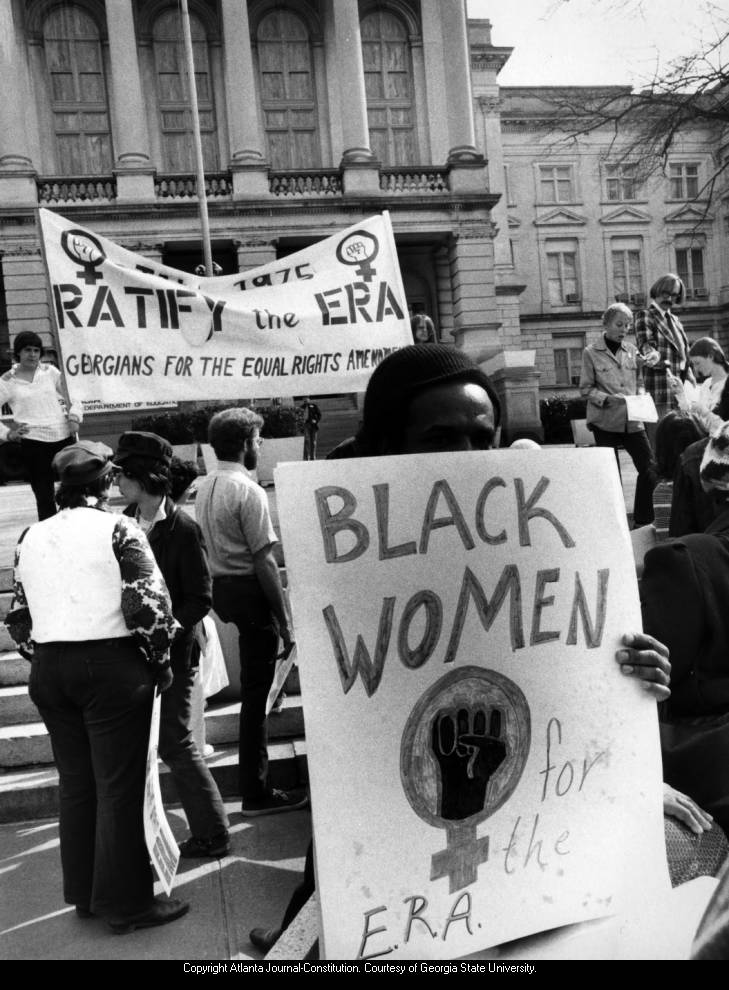

Taking the Chisholm trail

Morris: The show gets across that the pro-ERA and the feminist movement is struggling with these disagreements and these different visions of what liberation looks like. But then there’s the scene when Schlafly doesn’t want to alienate anyone for their racist language with the Louisiana delegation and the woman from Texas says “Well, I’m a little bit more folksy than you are.” First of all, the southern accents in the show were horrible. But that aside, Phyllis says, “we all have to speak with one voice.” Phyllis kept a tight reign on the language. When I interviewed her, I asked her how she got some of these religious groups to work together and not fight and she said “Well, I wouldn’t let them.” That was it, that was the answer. She might have welcomed racists into her movement, but they’re not going to talk about race. She never talked about race, but it’s always there and she will accept anyone into it. The first hearings on Georgia STOP ERA, I think it was ’73 or ’74, J.B. Stoner, who was the candidate for governor on the state’s rights ticket, got up and gave this racist testimony about why you don’t need the Equal Rights Amendment and Kathryn Dunaway was like “oh hell no!” well she wouldn’t have said that, she would have said “oh heck no!” After that she controlled who got to testify. She was picking the pretty women. She got mad because one of the old women got up there and talked too long, so the pretty stewardesses from Delta couldn’t get up there and talk. She would control it and they weren’t allowed to talk about race.

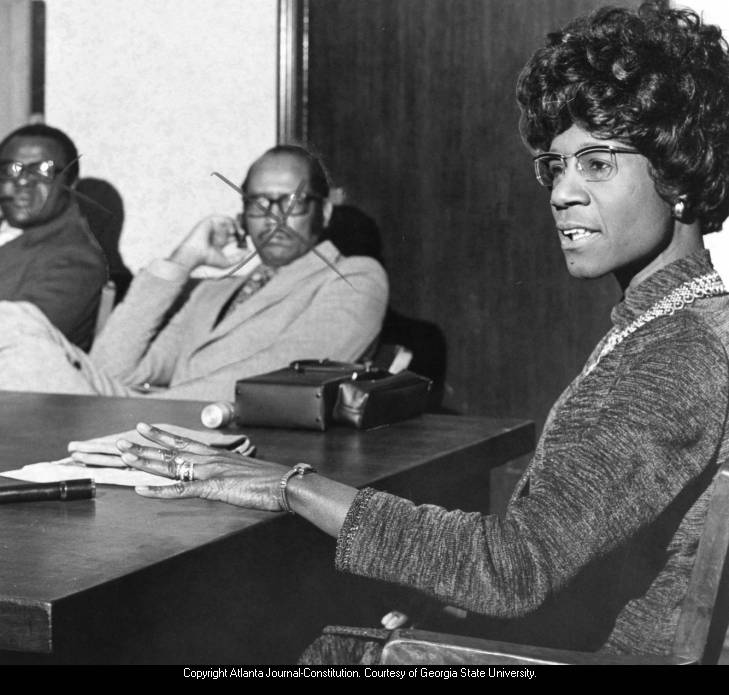

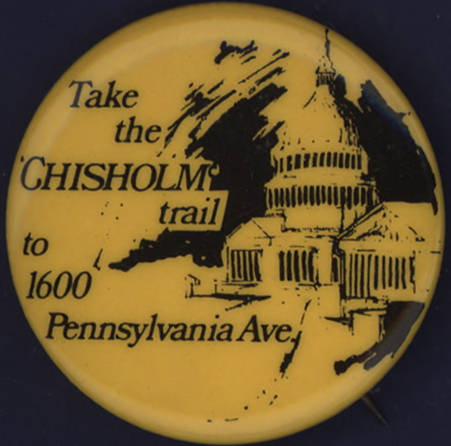

My forthcoming book Goldwater Girls to Reagan Women (University of Georgia Press) goes back a little bit further. The series probably won’t have much of this, but it includes some of the African American women who are trying to be involved with the Republican politics and keep getting pushed out. I do really love Niecy Nash as Flo Kennedy in this. I just wanna give a shout out to that, because she’s awesome! They’re showing race really interestingly, in the feminist movement. There’s not much race in STOP ERA, but I just want to acknowledge that…There’s a couple of historians working on Shirley Chisholm biographies, so you can look for those books coming out too. I love that she’s starting to get her recognition, which is long overdue.

Presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm on a campaign stop, 1972.

Morris: There’s a scene in the Shirley episode, episode 3, where they’re at the democratic convention and Betty, Shirley, Gloria, and Bella are all there signing books and I was like, damn, those are some badass women! I thought that was such a cool scene. Phyllis could also do that at her convention.

Gerrard: I have a little story about Shirley. Dewald, whose papers we have, she was very active with the democratic party. She and her husband live in my neighborhood, they hosted a party for Shirley. There were so many people there that the police arrived, so many people on their deck that the deck almost collapsed! There was a lot of support around here for her.

Concluding thoughts: it’s fun and validating to see this history brought to life!

Morris: I feel like my research is finally, like I’ve always been doubting does it have significance and I’m like IT DOES!

Harvel: When I told my friends I was doing an exhibit on the ERA they were like, what? The ERA, the Equal Rights Amendment. And they asked that thing from the 1970s?

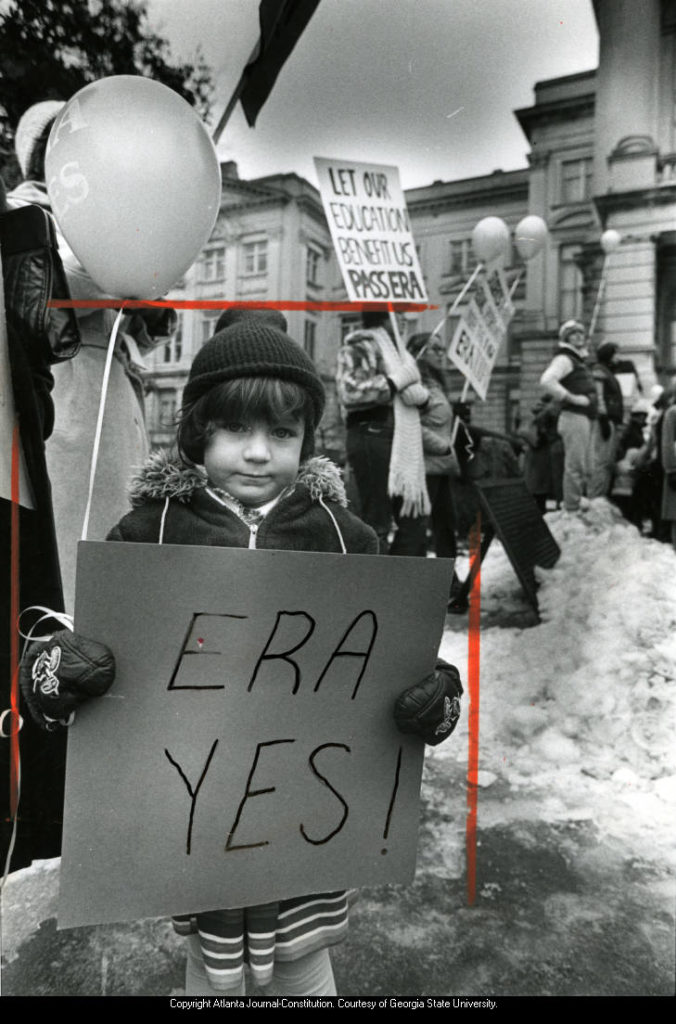

Equal Rights Amendment ratification supporter, five-year old Katie Coates, demonstrating outside the Georgia State Capitol building, Atlanta, Georgia, January 1982.

Harvel: And I was like, well kind of, but also now. So now I can be like just go watch the show.

Gerrard: I really enjoyed stuff that I had known about for such a long time and I’ve thought about and I tried to picture in my mind. It’s kind of fun to see it brought to life.

Morris: There’s this other part, with Gloria having an affair with a man. In Revolution from Within and even in her last book My Life on the Road, she talks about her lack of self esteem during the period that the show is portraying. It’s really interesting having that perspective on Gloria. She’s coming across so powerful and so strong, but I keep thinking of how she was writing about her insecurity at the time. I’m not sure if I’m projecting that or if that’s coming through in Byrne’s portrayal.

Gerrard: I feel like she’s got some frailty to her in the show. Her physicality, she kind of hunches a bit, her head is down a lot.

Morris: And she’s hanging her hair [over her face]. She’s aware of how she is coming up. There’s the great scene where she asks Bella, oh you only want me for my pretty face, and Bella basically says [no, I want your body too.] That’s who she was in the movement, she was the pretty one.

Harvel: It was cool seeing the Ms. Magazine launch party. Ms. Magazine is the first thing I ever looked at in the archives at GSU. So I really enjoyed that.