Making History, Writing History: Thoughts for Black History Month

We often hear the phrases “living through history,” “witnessing history,” “history in the making.” We are literally always creating what historians call “primary sources,” which can be any kind of resource that is made, written, drawn, filmed, built. Almost anything that is created can be interpreted as a primary source. Historians then use primary sources to create what are called “secondary sources,” which are scholarly books and articles that interpret primary sources, usually in the context of other secondary sources which provide background information and context. Because scholarly books and articles rely on the careful gathering and interpreting of primary sources, and usually involve some sort of peer review (“peer review” means that other scholars read a draft of the book or article to determine the soundness of its argument), scholarly treatments of particular events often take awhile to make their way into print.

In today’s media culture, however, there is no shortage of primary sources generated around a particular event as it unfolds. In late summer and autumn of 2014, after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, newspaper accounts and editorials abounded; Twitter, Vine, and other social media platforms also provided a wealth of real-time primary source materials. Washington University’s library created Documenting Ferguson, an online collection of the digital media captured by members of the Ferguson community after the August 9, 2014 shooting.

However, very little scholarship existed at that time on race relations in Ferguson or North St. Louis County. Immediately after the shooting, we posted several sources on this blog intended to help contextualize the history of race relations in St. Louis and St. Louis County, including one book, Daniel J. Monti Jr.’s Semblance of Justice: St. Louis School Desegregation and Order in Urban America (1985), which happened to be a case study of the Ferguson-Florissant School District’s mandatory desegregation, which took place in 1976, but which at the time was not even cataloged as being about the town of Ferguson, Missouri.

We have also seen the rise of blogging and other forms of writing, which can be treated as primary sources. But many scholars have also turned to blogging and social media platforms to use their expertise to interpret current events as they unfold. The Black Lives Matter movement, sparked by the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an African-American teenage boy, came to national attention kindled by the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner by police actions in Ferguson and New York City respectively.

At the same time, using hashtags on Twitter and other social media, scholars specializing in African-American Studies worked together to create various “syllabi” focusing on and contextualizing racially charged moments in recent American history. These syllabi often look like your own course syllabi: they are lists of books, articles, and other media sources designed to educate students and general readers about the context, history, and broader significance of challenging events, particularly those affecting groups whose history has been underrepresented or marginalized.

Some examples include:

- #FergusonSyllabus, a Twitter hashtag project conceived by Georgetown University history professor Marcia Chatelain in response to the protests in Ferguson following the police shooting of Michael Brown. A group of sociologists have also compiled a #FergusonSyllabus available here.

- #BaltimoreSyllabus: a Twitter hashtag begun in response to the death of Eric Garner and the protests that followed; see also the #BaltimoreSyllabus compiled here.

- #CharlestonSyllabus: a Twitter hashtag conceived by Brandeis University African-American history professor Chad Williams. Williams and other historians affiliated with the African American Intellectual History Society have coedited a book based on this syllabus, Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence (2016)

- #LemonadeSyllabus, a downloadable product created by Candice Marie Benbow, a doctoral student in Religion and Society at Princeton Theological Seminary and a Lecturer in Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University.

- #OrlandoSyllabus: a Google document of resources contextualizing the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

- #StandingRockSyllabus, created by the NYC Stands for Standing Rock committee, a group of indigenous scholars and activists and settler/people of color supporters in the New York area.

- There are also two versions of a #TrumpSyllabus. The original #TrumpSyllabus was published in the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the second, “Trump Syllabus 2.0,” was posted at Public Books in response to the syllabus published in the Chronicle.

These syllabi use social media to collect and disseminate expertise and information about difficult topics, while also highlighting the communities involved: the communities experiencing these events directly, the communities of educators assembling educational materials, and the broader communities of people in need of this information. These “syllabi” also highlight that the events they are teaching about are in themselves historical: they are history being made. At the same time, they represent positive action on the part of those assembling the syllabi and those using them to enhance their learning.

By 2014, scholarly works on Trayvon Martin had begun to appear, including:

- Kenneth J. Fasching-Varner, et al., Trayvon Martin, Race, and American Justice (2014)

- Lisa Bloom, Suspicion Nation: The Inside Story of the Trayvon Martin Injustice and Why We Continue to Repeat It (2014)

- Devon Johnson, et al., Deadly Injustice: Trayvon Martin, Race, and the Criminal Justice System (2015)

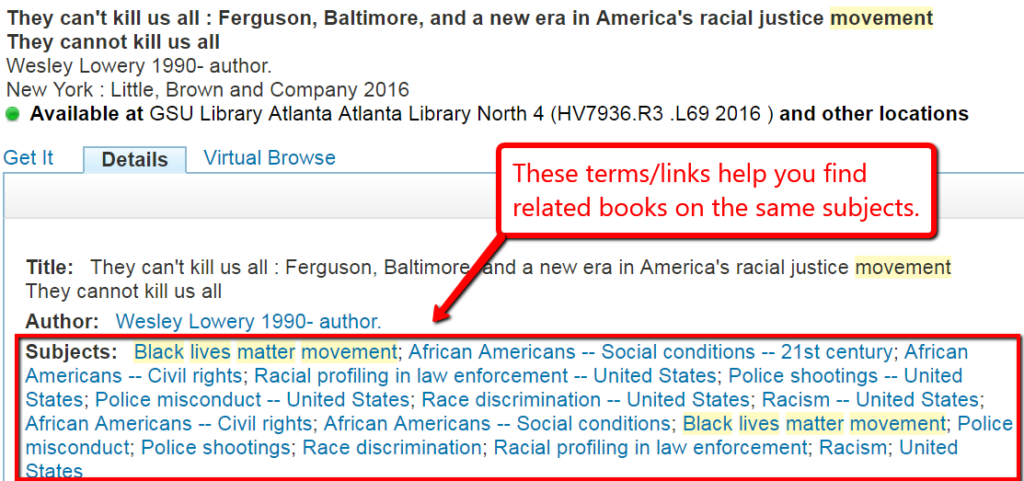

By now, enough time has passed since Ferguson that scholarly works on Black Lives Matter and the other sparking events are now coming into print. As time goes on, Black Lives Matter and the events that gave birth to it are being woven into American history. Relevant scholarship includes:

- Wesley Lowery, They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement (2016)

- Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (2016)

- David Wallace McIvor, Mourning in America: Race and the Politics of Loss (2016)

- Yuya Kiuchi, ed., Race Still Matters: The Reality of African American Lives and the Myth of Postracial Society (2016)

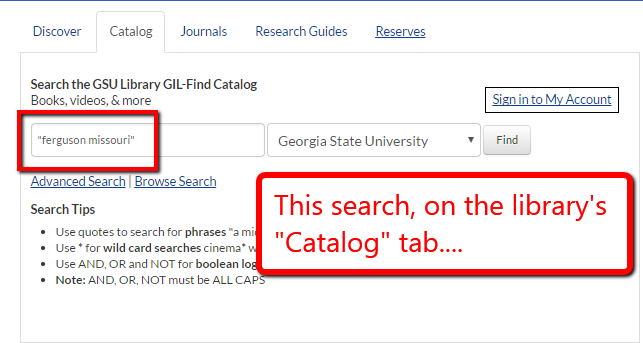

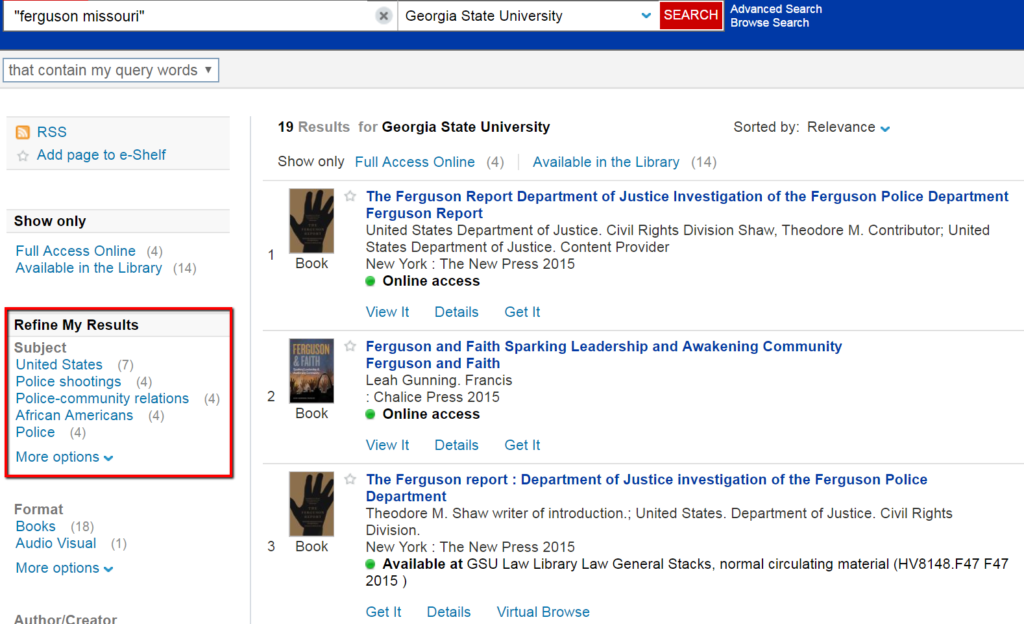

New subject terms evolve in response to developing events. “Martin, Trayvon, 1995-2012” is now a Library of Congress subject heading. Prior to August 2014, “Ferguson (Mo.)” was also a Library of Congress subject term, but searching on it would yield few results. Searching the library catalog for “Ferguson Missouri” as a subject now yields more results related directly to the unrest there. This search:

now leads to these results, as a starting point:

And “Black Lives Matter movement” is now also a Library of Congress subject term in its own right.

At the same time, primary sources continue to be generated that will contribute to historians’ (and our) understanding of current events. Examples of print sources that can be read as primary sources about Black Lives Matter might include:

- United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Human Rights, “Stand Your Ground” Laws: Civil Rights and Public Safety Implications of the Expanded Use of Deadly Force: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Constitution, Civil Rights and Human Rights, Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, first session, Tuesday, October 29, 2013

- United States. Department of Justice. Department of Justice Report Regarding the Criminal Investigation into the Shooting Death of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Missouri Police Officer Darren Wilson (2015)

- United States. Department of Justice. Civil Rights Division. Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department (2016)

- George Yancy et al., Our Black Sons Matter: Mothers Talk About Fears, Sorrows, and Hopes (2016)

- Lezley McSpadden, Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil: The Life, Legacy, and Love of My Son Michael Brown (2016)

We can still look to history (because African-American history is American history) to help contextualize this current movement, which is deeply rooted in longer strands of African-American history, linking to the civil rights movement, and, going even further back, the anti-lynching movement. Placing the Black Lives Matter movement within the context of historical African-American activism highlights African-Americans’ actions in support of community—actions which include the efforts of historians, archivists, and other scholars to preserve and protect African-American history as it is being made. African-American history is American history—every month.