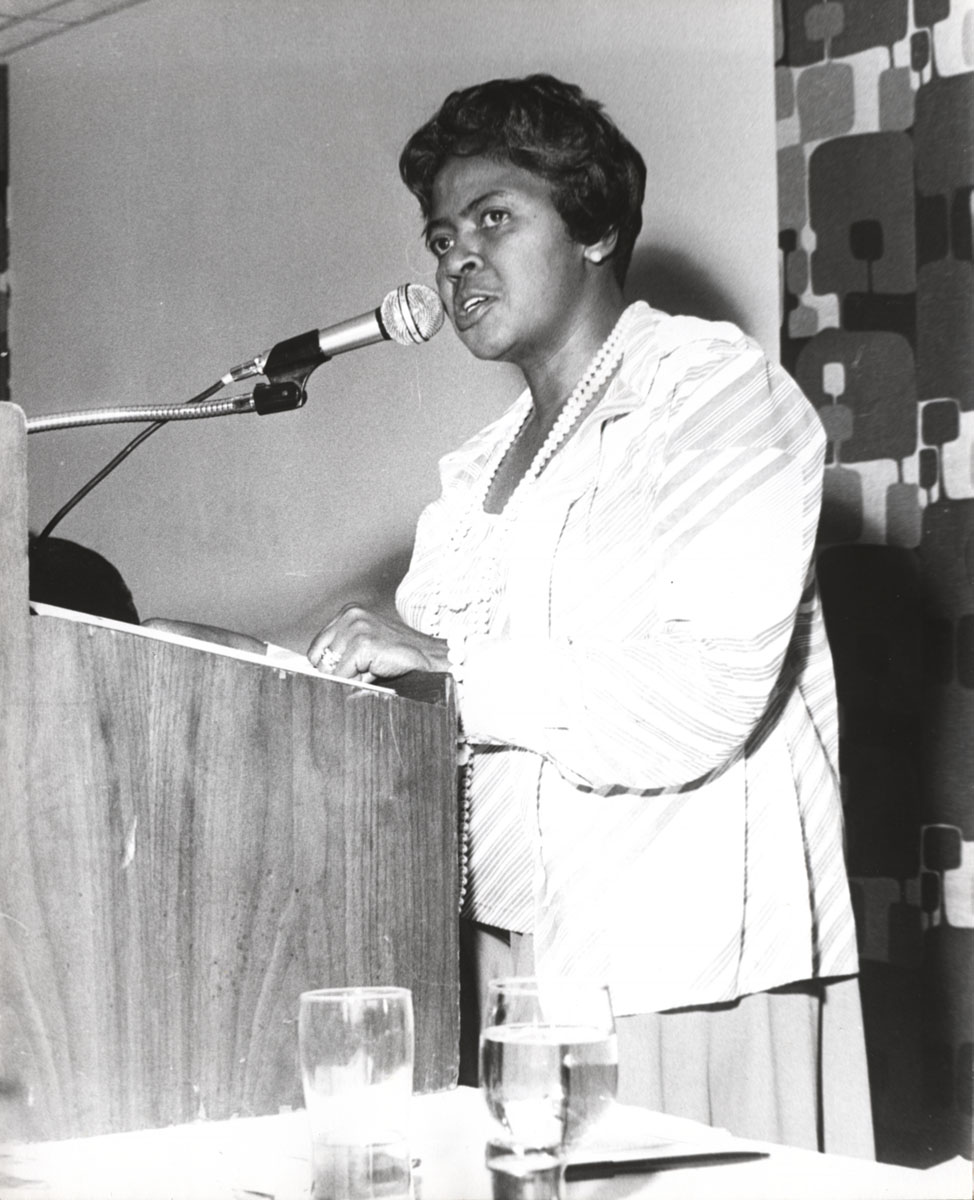

Dorothy Bolden gave voice to Atlanta’s “Help”

This is a guest blog from Daniel Horowitz Garcia, a graduate student currently enrolled in Georgia State University’s Department of History. He began researching the work of Dorothy Bolden while an undergraduate and received his B.A. in 2010. A brief conversation about the recently-released and very popular film, The Help, led him to offer to write this blog. Thanks, Dan!

In The Help one of the Black characters is regularly fired for talking back to her white employers. Central to this story set in 1960s Mississippi is the idea that standing up for oneself, especially if one is Black, can be dangerous. Dorothy Bolden would tell them all they don’t know the half of it.

Bolden became a domestic worker in the 1930s. In 1968 she founded the National Domestic Workers Union, the longest surviving organization of domestic workers in U.S. history. At its height the union claimed to represent 30,000 people and played a part in fundamentally changing the treatment of domestic workers under U.S. labor law. Bolden was at the center of a struggle that raised Atlanta wages by 33% in two years as well as won inclusion off all domestic workers in Social Security and workers’ compensation. However, her personal struggle started when she talked back to an employer and almost lost more than her job.

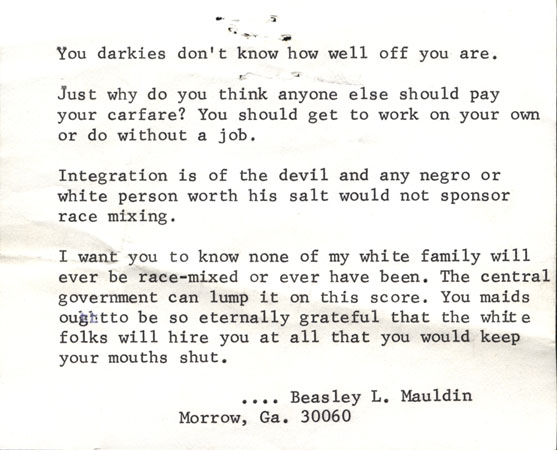

Bolden was radicalized on the job in the late 1940s. At the end of her work day she was heading out the door when her boss, a white woman, told her to wash the dishes. Bolden refused. A short time later Bolden was picked up by the police and taken to the county jail for a psychiatric evaluation. “They told me I was crazy because I had talked back to a white woman, and called in some psychiatrists to prove it,” said Bolden. “A white woman’s word was gospel, and two psychiatrists actually thought I was crazy… This was the way you got locked up…This was the system.”[1] Bolden’s uncle paid for an independent evaluation and prevented her from being institutionalized, but she was kept radical by the racial indignities of Black people’s daily lives. Before the mass re-emergence of the civil rights movement in the 60s she would regularly see young, white men accost Black domestic workers on their way home at night. The women, holding food given by their employer so they wouldn’t have to cook for their children at the end of the day, would have the food knocked out of their hand by bands of white teenagers.[2] These types of daily assaults and indignities left their mark on Bolden.

By the end of the 60s Bolden was already a seasoned community activist. By the mid-1960s she had fought to stop a Black school from closing in her neighborhood, had confronted police brutality, and had worked with almost all of the emerging Black civil rights leaders and organizations. She first decided to do something for domestic workers in 1965, but began organizing in earnest after talking with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. The NDWU lasted from 1968 to 1996. During almost three decades of work, despite the danger involved, Bolden and the other members of the union never stopped talking back.

Additional Resources

In Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library:

- The National Domestic Workers Union Records, Southern Labor Archives

- Interview with Dorothy Bolden, Voices of Labor Oral History Project

- Interview with Dorothy Bolden, Georgia Government Documentation Project

In the General Collections, Georgia State University Library:

- Oral history interview with Geraldine Roberts, Domestic Workers of America (1978)

- Between women: domestics and their employers, Judith Collins (1985)

- Not one of the family: foreign domestic workers in Canada, Abigail Bakan (1997)

- Telling memories among southern women: domestic workers and their employers in the segregated South, Susan Tucker (1988)

- And more…

At Auburn Avenue Research Library, Atlanta, Georgia:

- The Dorothy Lee Bolden Thompson Collection at Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History, a Special Library of Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System

[1] George Coleman, “Domestic Work Now a Virtue Because of Dorothy Bolden,” National Domestic Workers Union (U.S.) records, Southern Labor Archives, Georgia State University Library, Atlanta, Georgia.

[2] Chris Lutz, “Interview with Dorothy Bolden, 08/31/95, 95-12, August 31, 1995,” Voices of Labor Oral History Project, Atlanta, 22.