St. Elmo Murray, Byronic Hero?

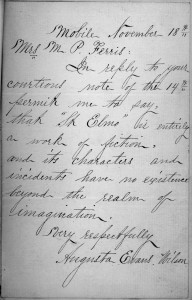

Born Augusta Jane Evans on May 8, 1835, in Wynnton (now the MidTown area in Columbus), Georgia, Mrs. Augusta Evans Wilson (1835-1909) wrote nine highly successful novels, but her St. Elmo was among the most popular works of American fiction published between Reconstruction and World War II. The highly romantic tale of devout heroine Edna Earl, her unending struggles to establish a writing career, her tiresome crusade to maintain a rigid code of Christian conduct, and her tedious refusal to marry any man not equal to her Christian standards sold one million copies in the first four months after its publication in 1866. Income from the sale of Wilson’s novels made her the first female author to earn $100,000 from royalties. This record was not matched until Edith Wharton in the 1920s. The influence of Wilson’s novel cannot be underestimated: whole towns were named or re-named “St. Elmo,” as were steamboats, cigars, hotels, dogs, flowers, and (unfortunately) newborn boys. Mrs. Wilson carried on a lively correspondence with friends and readers, and the Rare Book Collection in Special Collections and Archives holds one such unpublished letter written to reader Mrs. M.P. Ferris, sometime after Wilson’s marriage in 1868. In this letter, we see the keen interest the American public had in Mrs. Wilson’s fictional characters, particularly the character of the book’s hero and namesake, St. Elmo Murray.

If Edna Earl is a devout Christian, certainly hero St. Elmo must be described as anything but devout. In fact, he fits very nicely into the tradition of the Byronic hero. Edna first encounters St. Elmo, and

…the first glimpse of him filled her with instantaneous repugnance; there was an innate and powerful repulsion which she could not analyze. […] His features were bold but very regular; the piercing, steel-gray eyes were unusually large, and beautifully shaded with long, heavy, black lashes, but repelled by their cynical glare; and the finely-formed mouth, which might have imparted a wonderful charm to the countenance, wore a chronic, savage sneer, as if it only opened to utter jeers and curses. Evidently the face had once been singularly handsome, in the dawn of his earthly career, when his mother’s good-night kiss rested like a blessing on his smooth, boyish forehead, and the prayer learned in the nursery still crept across his pure lips; but now the fair chiseled lineaments were blotted by dissipation, and blackened and distorted by the baleful fires of a fierce, passionate nature, and a restless, powerful, and unhallowed intellect. Symmetrical and grand as that temple of Juno, in shrouded Pompeii, whose polished shafts gleamed centuries ago in the morning sunshine of a day of woe, whose untimely night has endured for nineteen hundred years; so, in the glorious flush of his youth, this man had stood facing a noble and possibly a sanctified future; but the ungovernable flames of sin had reduced him, like that darkened and desecrated fane, to a melancholy mass of ashy arches and blackened columns, where ministering priests, all holy aspirations, slumbered in the dust. His dress was costly but negligent, and the red stain on his jacket told that his hunt had not been fruitless. (St. Elmo, 1867, p. 52-53)

Of course, as befits a proper romance novel, St. Elmo gets religion, becomes a minister, and marries Edna.

Lord George Gordon Byron (1788-1824), the highly romanticized English poet, set the mark for the bad-boy character that bears his name, the “Byronic hero.” The pantheon of Byronic heroes includes such figures as Captain Wentworth (Jane Austin’s Persuasion), Heathcliff (Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights), Rochester (Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre), Dorian Gray (Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray), Lestat (Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire), Severus Snape (J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books), Angel (television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer), and Q (film and television Star Trek). Even teen idol Elvis Presley was viewed as a slightly dangerous hero with a troubled past, and his being drafted into the army in 1958 caused a national sensation. During World War II, in 1943, romantic lead Tyrone Power enlisted in the U.S. Marines, attending flight-training school in Atlanta the following year. The photograph to the left of the classic, swarthy Byronic hero (Power could easily have played the role of St. Elmo Murray) was recently discovered in the Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers collection.

Augusta Evans Wilson’s St. Elmo does not fit the 21st-century’s criteria for great literature, and her piety and gratuitous erudition can be cloying. In fact, even in its own time, St. Elmo provoked critical disdain. Two years after its publication, Charles Henry Webb (1834-1905), known as “John Paul,” published a brief parody of St. Elmo titled St. Twel’mo, or, The Cuneiform Cyclopedist of Chattanooga (1868). Webb’s heroine swallows an unabridged dictionary, enabling her to spout profuse erudition. Despite critical opinion, in the case of Mrs. Wilson, popular taste won out, and St. Elmo was made into several stage plays (first in 1909, and most recently, 1996), as well as at least two silent films (1914, and the popular 1923 version, starring aptly-cast John Gilbert as St. Elmo Thornton).

For students and researchers, Wilson’s novels provide enormous possibilities for research into 19th-century American social life, history, literary tastes, architecture, gardening, theology, philosophy, publishing, and art. This realization has not been lost in academic circles; most of Wilson’s novels are available freely in digital form on the Internet. The University of Alabama has digitized a number of her letters, and the secondary literature in print and online has grown rapidly. Combined with the resources in Special Collections and Archives, themes in Wilson’s romances offer opportunities for interdisciplinary research and presentation.

Have a Look: Resources

- Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875, provides many full-text digital copies of 19th-century authors, including Augusta Evans Wilson.

- Fidler, William Perry. Augusta Evans Wilson, 1835-1909: A Biography. [University, Ala.]: University of Alabama Press, 2003, 1951.

- Evans, Augusta J, and Rebecca Grant Sexton. A Southern Woman of Letters: The Correspondence of Augusta Jane Evans Wilson. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002.

- Riepma, Anna Sophia Roelina. Fire & Fiction: Augusta Jane Evans in Context. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000.

- Thorslev, Peter L. The Byronic Hero: Types and Prototypes. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962.

- Stein, Atara. The Byronic Hero In Film, Fiction, and Television. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.