Is banning books a thing?

This week (Sept. 23-29) is #BannedBooksWeek

Now celebrated annually, Banned Books Week was started in 1982 “in response to a sudden surge in the number of challenges to books in schools, bookstores and libraries,” and its purpose is to “bring together the entire book community — librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers of all types — in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular” (2018 Banned Books Week website).

Each year the American Library Association (ALA) Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF) compiles lists of challenged books. Below are the Top Ten Challenged Books of 2017, with links to catalog records where you can either check the book out from any GSU campus library, request it from another University System of Georgia (USG) library, or request it via ILLiad interlibrary loan from a non-USG library:

- Thirteen Reasons Why written by Jay Asher

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian written by Sherman Alexie

- Drama written and illustrated by Raina Telgemeier

- The Kite Runner written by Khaled Hosseini

- George written by Alex Gino

- Sex is a Funny Word written by Cory Silverberg and illustrated by Fiona Smyth

- To Kill a Mockingbird written by Harper Lee

- The Hate U Give written by Angie Thomas

- And Tango Makes Three written by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson and illustrated by Henry Cole

- I Am Jazz! written by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings and illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas

Banning books — is it a thing?

Given there’s an entire week bringing attention to attempts at censoring books in the US, we might jump to the conclusion that tons of people are running around trying to remove books from libraries. But let’s pause and ask ourselves, “I wonder if there’s data that examines US people’s attitudes about removing books from libraries?” Well, as luck would have it, there is!

The General Social Survey, or GSS for short, which has been conducted approximately every other year since 1972, tracks hundreds of trends in social characteristics and attitudes over the past four decades. While not a survey of the entire US population, it is a full-probability, national-level sample survey — in layman’s terms, that means you can be pretty confident that the opinions of the group of people surveyed in any given year generally reflect those of the US population at that time.

The General Social Survey, or GSS for short, which has been conducted approximately every other year since 1972, tracks hundreds of trends in social characteristics and attitudes over the past four decades. While not a survey of the entire US population, it is a full-probability, national-level sample survey — in layman’s terms, that means you can be pretty confident that the opinions of the group of people surveyed in any given year generally reflect those of the US population at that time.

The GSS includes a series of questions that asks participants if they “favor removing” a book from the public library for various reasons, including but not limited to the following:

- a book that is “against churches and religion” [GSS variable LIBATH, asked 1972-2016]

- a book written by “a man who admits that he is a homosexual” that is “in favor of homosexuality” [GSS variable LIBHOMO, asked 1973-2016]

- a book written by a Muslim clergyman that “preaches hatred of the United States” [GSS variable LIBMSLM, asked since 2008]

- a book that claims “Blacks are [genetically] inferior” [GSS variable LIBRAC, asked 1976-2016]

Click on the variable name links above to explore the general trends in attitudes over the years.

But wouldn’t personal characteristics influence someone’s attitudes about removing books from libraries?

Great question! In statistics language: you want to see if various independent variables (e.g., race/ethnicity, religion, political views, sexual and/or gender identity, library use, etc.) have an effect on the dependent variables of removing books from libraries for various reasons. If you don’t feel like playing with the GSS data yourself, you’re in luck that some recent researchers explored this question using the GSS data:

- Brett, J., & Campbell, M. E. (2016). Prejudices unshelved: Variation in attitudes toward controversial public library materials in the General Social Survey, 1972–2014. Public Library Quarterly, 35(1), 23–36.

- Burke, S. K. (2010). Social tolerance and racist materials in public libraries. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 49(4), 369–379.

- Burke, S. K. (2008). Removal of gay-themed materials from public libraries: Public opinion trends, 1973-2006. Public Library Quarterly, 27(3), 247-264.

If you do want to explore the GSS data yourself, there are a couple of online tools for doing so:

- SDA (Survey Documentation and Analysis) tool — short video help tutorials

- GSS Data Explorer — help resources

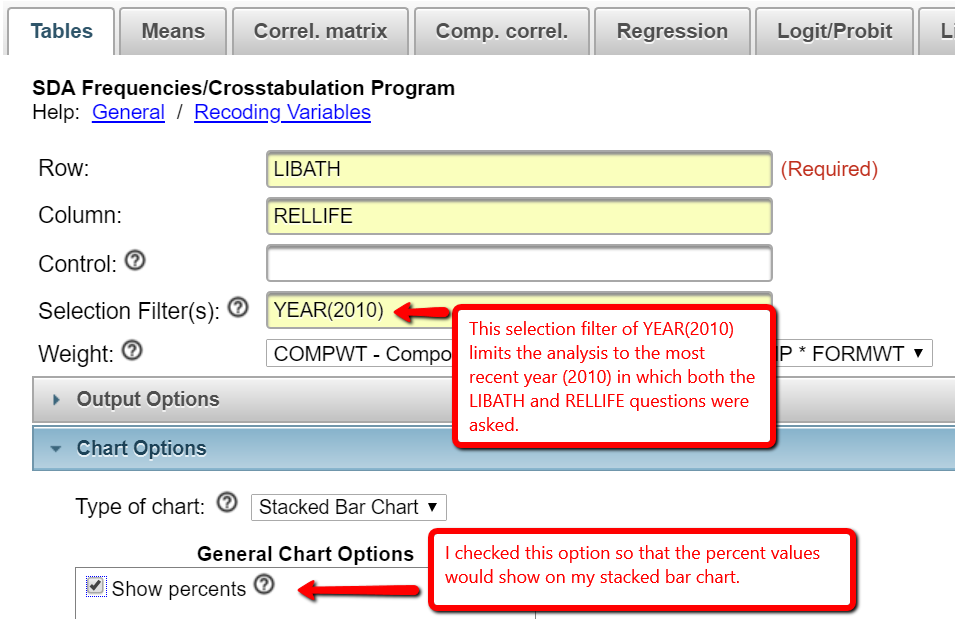

For example, I was curious to explore if one’s opinions about removing a book “against churches and religions” [GSS variable LIBATH] would be influenced by that person’s religious beliefs. Rather than use the same independent variables that the articles above had used for their religion measure, I used the SDA online tool and found the following question:

- Please tell me whether you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statement: I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my other dealings in life [GSS variable name RELLIFE, asked last in 2010]

I used the SDA online tool to set up a crosstabs table to explore the relationship between these two variables:

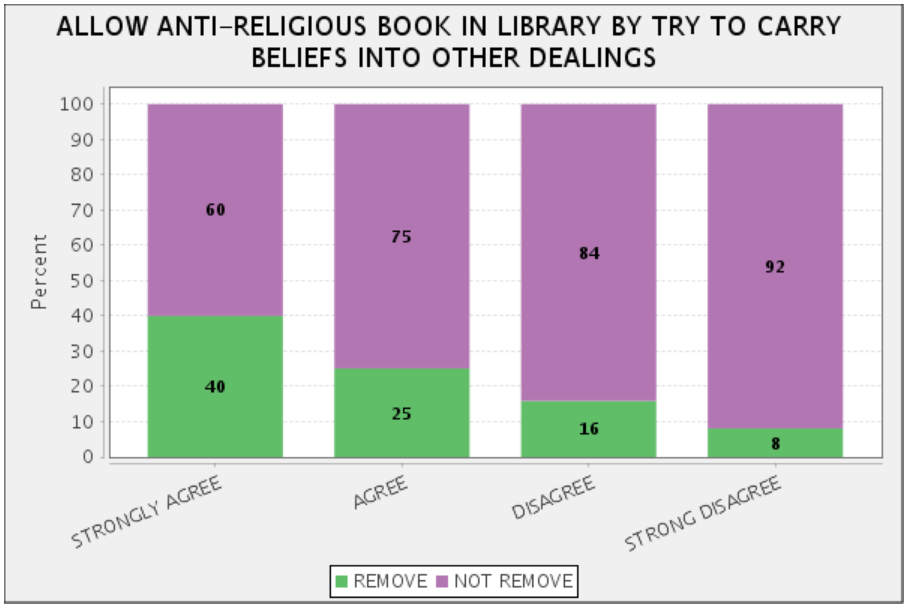

After clicking the Run the Table button, another browser tab opened with: (1) a table containing the percentages (in bold) and counts broken down by question answer for the 1,239 people in 2010 who answered this question, and (2) a stacked bar chart displaying the percentages broken down by question answer. To save space I’m just going to include the stacked bar chart below for our interpretation:

What does this chart seem to tell us about the relationship of these variables?

- Start at the right side of the chart and focus on the green sections of the bars. As we move from right to left across the horizontal axis from respondents saying they ‘strongly disagree’ to those saying they ‘strongly agree’ with the statement “I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my other dealings in life,” we see a steady increase in the percentage of GSS participants who thought a book “against churches and religions” should be removed from the public library. In other words, this data supports a claim that, generally, the more a person tries to carry their religious beliefs into their everyday life, the more likely they are to say an anti-church/anti-religion book should be removed from the public library.

- That said, if we focus on the purple section of the bars, we should note that 60% of those that strongly agreed and 75% that agreed with the statement “I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my other dealings in life” did *not* think that an anti-church/anti-religion book should be removed from the public library. So, this data supports a claim that, generally, even if people feel that their own religious beliefs should factor into their everyday life, they are more likely to be tolerant of anti-church/anti-religion ideas being available in public library books than they are to wish that the books be removed/censored.

Want to dig into this or other data even deeper?

If we downloaded this data into a statistical software package like SPSS, SAS, or R to run tests of statistical significance, we could make more definitive conclusions about the relationship between these two variables as well as factor in other variables. Sound like fun? If so, the Library’s Research Data Services Team can help you find data and learn how to use tools to analyze it. We want to arm you with data for success in your academic life and beyond!