To Learn More: Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (1853)

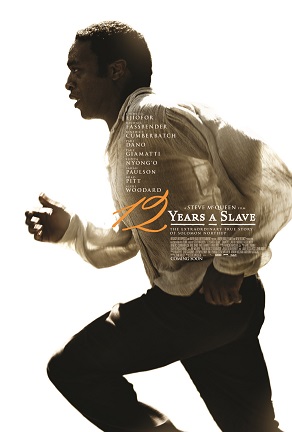

Last night the film Twelve Years a Slave, a wrenching portrait of a free black man kidnapped into slavery, won the Oscar award for Best Film; the film’s director, Steve McQueen, became the first black director to win for Best Film (though he was overlooked for Best Director). Lupita Nyong’o also won Best Supporting Actress for her role, and John Ridley won Best Adapted Screenplay for the film. Twelve Years a Slave has received strong critical acclaim and other accolades, including the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture—Drama and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA)’s Best Film award; BAFTA also gave the film’s star, Chiwetel Ejiofor, the award for Best Actor.

Last night the film Twelve Years a Slave, a wrenching portrait of a free black man kidnapped into slavery, won the Oscar award for Best Film; the film’s director, Steve McQueen, became the first black director to win for Best Film (though he was overlooked for Best Director). Lupita Nyong’o also won Best Supporting Actress for her role, and John Ridley won Best Adapted Screenplay for the film. Twelve Years a Slave has received strong critical acclaim and other accolades, including the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture—Drama and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA)’s Best Film award; BAFTA also gave the film’s star, Chiwetel Ejiofor, the award for Best Actor.

Twelve Years a Slave was based on the memoir of Solomon Northup, published in 1853. Northup, born free in New York state in 1808, was kidnapped in Washington, DC in 1841 and sold into slavery. Northup remained enslaved in Louisiana for twelve years. With the assistance of the state of New York and a local Louisiana attorney, Northup’s father’s former owner Henry Northup was able to free Solomon Northup, who went on to write his memoir. He filed kidnapping charges, but the case was dropped due to legal technicalities, and he was never remunerated; Northup is believed to have died in 1863 (for this and more detailed information about Northup’s life, see the Summary at Documenting the South’s record for the memoir). The original New York Times article, dated January 20, 1853, describing Northup’s “seizure and recovery” available here.

Solomon Northup’s memoir Twelve Years a Slave was published in 1853 by Derby & Miller of Auburn, New York, not long after the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Northup’s story was recorded by a white lawyer and legislator from New York; it was dedicated to Harriet Beecher Stowe and introduced as “another Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” referring to Stowe’s 1853 publication A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, whose long subtitle began “Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon which the Story is Founded.” The book sold over 30,000 copies, which was enough to qualify the book as a best-seller in its time.

Slave narratives were a not uncommon genre during the antebellum decades; Northup’s narrative takes its place along several other important slave narratives, including but not limited to:

- Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1860)

- William Wells Brown’s Narrative of William W. Brown, an American Slave. Written by Himself (1849)

- John Andrew Jackson, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (1862)

- Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself (1845), which Douglass revised several times.

- Jacob D. Green, Narrative of the Life of J. D. Green, a Runaway Slave, from Kentucky, Containing an Account of His Three Escapes, in 1839, 1946, and 1848 (1864)

Brown’s and Douglass’ statement “Written by Himself” underscores the complicated relationship many slaves had with literacy, since many Southern states passed laws prohibiting teaching slaves to read or write. Douglass and Jacobs both highlight the transformative effect that learning to read and write had on them. Many published slave narratives included statements of authentication written by influential whites, often abolitionists or others active in antislavery activities, attesting to the the authenticity of the stories contained.

Because these slave narratives were published in the nineteenth century, the originals are in the public domain and can be freely digitized. The links to the slave narratives listed above are to digitized originals in the University of North Carolina’s Documenting the South digital library; the Harriet Beecher Stowe links are to full-text digital originals in the HathiTrust digital library.

However, like many other important texts from earlier times, scholars have published annotated editions of these narratives: “annotated” means that the scholar/editor has provided extra information explaining contextual and other background information to help clarify the story of the text for contemporary readers; annotations are often represented as footnotes. Scholarly editors may also edit the text for clarity; in earlier times, an editor may have abridged a work (that is, shortened it, or left things out that that editor deemed irrelevant), so it’s important to pay attention to whether an edition of a book is identified as “abridged.” Annotated editions typically are not available to be digitized and made freely available; while the nineteenth-century texts themselves are in the public domain, the annotations are more current and so are not in the public domain. Annotated editions may be available as ebooks for purchase, by a library or by an individual.

In the case of Twelve Years a Slave, this kind of scholarly editing played a key role in the book’s continuing relevance to US history and in the creation of the award-winning film. In her post in the American Antiquarian Society‘s scholarly blog Common-Place, Mary Niall Mitchell describes her research into the editorial history of Twelve Years a Slave: not just its original publication in 1853, but its later republication by Louisiana State University Press in the late 1960s, by historians Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon. Eakin read Twelve Years a Slave as a child while traveling with her father to Oak Hall Plantation; the book was given to her by the grandson of a slaveowner mentioned in Northup’s book. Eakin was unable to buy a copy for herself, since the book had been long out of print. She began to trace the life of Northup while a college student at Louisiana State University in the 1940s, and in the 1960s, with the rising interest in African-American history, she, Logsdon, and the LSU Press brought an annotated version of Twelve Years a Slave into print. Mitchell provides an engrossing account of this process in her Common-Place post.

The GSU Library holds several versions of Twelve Years a Slave, including

- a 2007 reprint of the 1968 edition published by Eakins and Logdson

- Northup’s story collected along with narratives by William Wells Brown and Henry Bibb

- a copy of the original on microfilm (for those who enjoy reading on microfilm!)

We also have several books about Northup and his narrative, including:

We also have several books about Northup and his narrative, including:

- David Fiske, Clifford W. Brown, and Rachel Seligman, Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave (2013)

- Carver Wendell Waters, Voice in the Slave Narratives of Olaudah Equiano, Frederick Douglass, and Solomon Northrup [sic] (2002)

We also have several other scholar-edited publications/collections of the antebellum slave narratives mentioned above: you can find these by using Advanced Search in the library’s catalog to search by both author and title. You can also find other slave narratives by using the term “Slave narratives” to do a subject-term search.

Finally, to learn more about the slave narrative in American history and culture, we have these books, among others:

- Audrey Fisch, ed., Cambridge Companion to the African American Slave Narrative (2007)

- Lee, Julia Sun-Joo, American Slave Narrative and the Victorian Novel (2010)

- Agnel Barron, Representations of Labor in the Slave Narrative (2009)

- Renee K. Harrison, Enslaved Women and the Art of Resistance in Antebellum America (2009)

Corrected: Steve McQueen is British, not African-American; he is the first black director to win an Oscar for Best Film.

Updated: added original 1853 New York Times article.