MLK’s Labor Legacy began in Atlanta

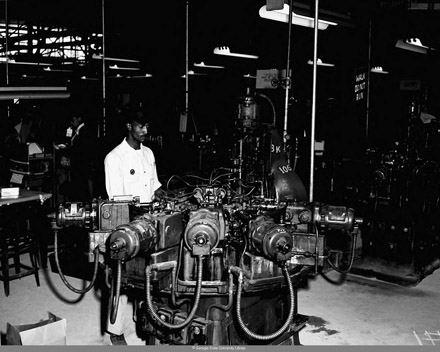

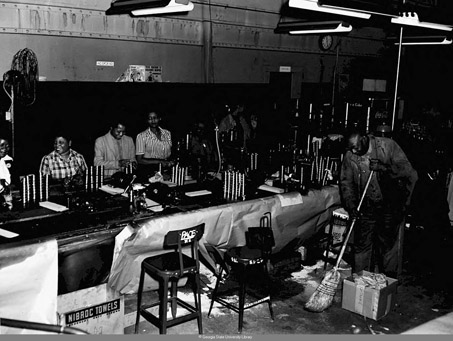

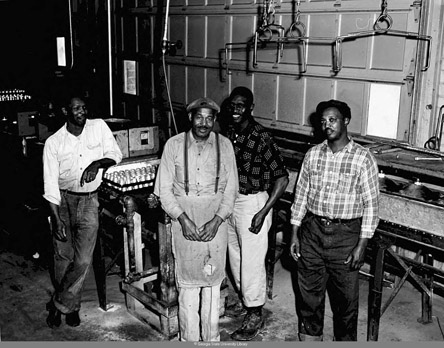

Yesterday, Creative Loafing online posted a photo essay titled “Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta” to commemorate Dr. King’s legacy and his ties to the city. The essay discusses the places he lived, worked, planned, and agitated, including the former site of Atlanta Scripto, one of the United States’ leading pen and pencil manufacturers and one of Atlanta’s largest employers. Creative Loafing used the Scripto Strike records, part of Georgia State University Library’s Southern Labor Archives, while researching their story.

In 1963, the International Chemical Workers Union began the process of organizing Scripto’s workers, and on June 9, 1964 the National Labor Relations Board granted the Chemical Workers Union a Certification of Representation. On the day before Thanksgiving, 1964, Scripto employees walked off the job, demanding more equitable pay for skilled and non-skilled workers. (As it stood, non-skilled workers were receiving $400 a year below the federal poverty level).

Dr. King sympathized with and supported the strikers, many of whom were black and members of King’s church. The Reverend C.T. Vivian believed an alliance between civil rights groups and the union would help the strikers reach their demands. With the help of King and Vivian, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Chemical Workers Union combined efforts to increase pressure on Scripto. They planned a national boycott, in which over half a million leaflets were distributed to unions asking them to boycott all Scripto products. As the strike progressed, it increasingly took the form of a civil rights initiative. By Christmas 1964, Scripto and the Union reached their first agreement: The union would drop the boycott, if Scripto gave the striking workers their annual Christmas bonuses. On January 9, 1965, the Scripto strike came to an end. The workers received a 4 cent across-the-board increase each year for the following three years, and Scripto was forced to re-hire 155 strikers and retain the replacement workers they had hired to maintain production during the strike. After the strike, racial tensions eased at the Scripto plant.*

This was Dr. King’s first showing of support for laborers, and he worked to form an alliance between the civil rights movement and labor unions until his assassination on April 4, 1968. At the time, he was in Memphis supporting striking sanitation workers, members of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Local 1733.

For more information about the Scripto strike and Dr. King’s ties with the labor movement, check out these resources:

Scripto Strike records, Southern Labor Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Scripto Pen Company records, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center (don’t forget the photographs!).

Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection, Atlanta University Center (AUC) Woodruff Library.

All labor has dignity, King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968 (speeches; other author: Honey, Michael K.), 2011.

Going down Jericho Road : the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King’s last campaign, Honey, Michael K., 2007.

I am a Man, web exhibit created by the Walter P. Reuther Library in conjunction with the Wayne State University Library System, which documents Dr. King’s trip to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968 to support striking sanitation workers, members of AFSCME Local 1733 (2012).

*“The Scripto Strike. Martin Luther King’s “Valley of Problems”: Atlanta, 1964-1965.” Atlanta History, Fall 1999.